The Underdog Curve

Chapter 8 - Entering The Underdog Curve

“Without continual growth and progress, such words as improvement, achievement, and success have no meaning.” —Benjamin Franklin

Five Phases of Personal Performance

Imagine for a moment that you are responsible for the successful operation of a typical wheelbarrow. This wheelbarrow happens to be fi lled to the brim with all your hopes, dreams, fears, and aspirations. Your singular goal is to move the wheelbarrow smoothly and consistently down the road laid out before you. You can make whatever enhancements, tune-ups, or improvements you like. The one rule is that you can never abandon it.

It’s heavy, very heavy. There is only one distinguishing characteristic about your personal wheelbarrow: instead of a round rubber tire like most wheelbarrows have, yours has a pentagonal, solid steel wheel.

As you start out, it doesn’t seem too heavy or cumbersome. The five-sided wheel is noticeable but feels manageable. The going is slow, but steadily, one thud at a time, you push your wheelbarrow forward. It’s hard work. You slowly make progress down the road. The part of the road you can see looks like a slow, steady gradual incline. You say to yourself, “I’ve got this. If I give it one little push at a time, I’ll get to where I’m heading.” As you continue, it gets harder to make progress, as every flip of the tire gets a little heavier and a little harder. As you stop to take a break, you think to yourself, “The grade of the road seems to be getting a little steeper,” but you put your head down and resume the pushing and the thudding. Sometimes there are brutal winds, rain, sleet, and even snow. These make it even more challenging to make progress. That damn metal wheel is not an all-terrain tire, for sure.

Eventually, an outgoing woman catches up to you on the road. She, too, has a wheelbarrow. Hers is filled with similar things to yours, things like hopes, dreams, fears, achievements, and aspirations for her own life. She can’t help but hear the thud of your wheelbarrow and notices your odd wheel. Seeing your plight, the woman stops her wheelbarrow and springs into action, digging through her mound of goodies, looking for a spare round rubber tire she knows she has tucked somewhere in her things. Actually, she says she has a couple of spares and knows this will help you solve that pesky thudding problem you have. Meanwhile, you keep plodding along while she looks for a new tire for you.

A few minutes later, the lady finds the tire, catches up, and offers it to you. She even offers to help you change the tire out. You say, “Thanks, but no thanks.” You’re busy. You’ve got your head down with enough work already moving your wheelbarrow forward. You think to yourself, “I don’t have time for distractions or delays like stopping to change a tire. The only way I can get ahead is to keep plugging along with what I’ve got. How could this lady possibly think I’m even open to the idea of stopping to change my tire?” But the tire lady decides to give you the tire anyway, placing it in your wheelbarrow as she takes off smoothly down the road ahead of you on her efficient, round, smooth little rubber tire. You think, “Geez, thanks. Now my wheelbarrow is even heavier.” And you keep thudding slowly along on that same old tire. As you look up you can see the woman disappearing into the distance, and you consider how light her load must be and how fortunate she is to have a rubber tire on her wheelbarrow in the first place. Some people have all the luck.

The irony of this story is that this is exactly how many of us behave. (I think my personal tire was square for a while, if I’m honest.)

As we move through life, there are a few aspects we do not understand. First, we underestimate the incline of the road ahead of us. It isn’t a gradual incline like it originally seemed. The truth is, it gets very steep at times. The sun doesn’t shine every day; sometimes it rains or snows on us. Then, when people reach out offering to give us a hand, we decline their help, because of pride, ego, or some deluded sense of self-reliance or pure stubbornness. We’re either far too proud to consider the help of others, or worse, we’re too preoccupied with a single-minded focus on using what we have to consider change in the first place.

When we think about our own personal performance, we often envision life as though it progresses on some slightly inclined but straight line. Unfortunately, that’s an overly simplistic and unrealistic view. It is also not how things work in the real world. Life doesn’t happen in a linear manner—there are ups and downs, U-turns, lefts, rights, and reversals. Our performance often corresponds accordingly.

There are numerous phases we go through in our personal journey. We learn, grow, and expand our views over time. Since these changes happen gradually and build on each other, it can be difficult to appreciate or recognize them on-the-fly. Left unchecked, gradual perspective shifts can lead to unintentionally entering phases of life that we aren’t ready to enter, are ill-prepared for, or would prefer to avoid altogether if we were only aware of them.

Now, I’m not a big fan of watching baseball, unless it’s used as a nice way to take a nap. I find it far more enjoyable to play than to watch, especially on television. There is, however, an interesting rules interpretation unique to baseball, which clarifies responsibility for player mistakes. For example, when a player drops a ball or makes a mistake due to the pressure applied by an opponent, it is called an error. When that same player is responsible due to either poor judgment or their own physical mistake for a play, it is known as an unforced error. It’s a nicer way of saying the error was avoidable, instead of “you screwed up.” In other words, avoidable errors are of our own doing. They can be mitigated and thus avoided. They are avoidable.

In chapter 6 we examined two significant areas where underdogs stumble—risking everything unnecessarily or exposing the chip on their shoulder. Underdogs have enough to deal with when it comes to surmounting existing adversity. They don’t need to add insult to injury by causing unforced errors in their own lives too. As we consider our external performance, this idea of risking everything and starting over surfaces again in how we decide to explore these new opportunities.

Fundamental Performance Curve

Personal performance graphs are a dime a dozen, and plenty has been written over the years on the idea. Everyone seems to have a theory. The details and the graph are less important than the idea they convey. Borrowing on the work of others over the years, I have a version to propose too. Ours is focused on creating a visually digestible and useful illustration that underdogs can lean on and practically implement. Having a visual starting point for our performance is nice because it gives us something to build our forthcoming framework around in the next section.

In its simplest form, there are typically five phases to personal performance. I call this the Fundamental Performance Curve (FPC). The five distinct phases are known as follows:

• Development

• Improvement

• Proficiency

• Declination

• Renewal

In each area of our lives, we progress through a version of these incremental stages over time. Think about your fi tness, fi nances, relationships, or sex life. The amount of time we spend in each phase of our performance depends on numerous factors. As we outlined in the last chapter, our performance includes things like our level of engagement, innate abilities, skill development, affi nity for learning, and more.

The FPC is straightforward. It’s important to wrap our heads around this illustration and characterization of each phase because we will be building on this basic framework to build out the underdog curve.

In the meantime, here’s a little more on the fi rst four phases of personal performance, including a visual illustration shown in f i gure 8.1:

Phase 1. Development: characterized by innate talent, education, knowledge development, personal discovery, uncertainty, confusion, curiosity, and trial and error.

Phase 2. Improvement: characterized by personal skill development, self-confi dence, self-awareness, perspective discovery, and the establishment of a sense of self.

Phase 3. Profi ciency: characterized by situational awareness, clarity, savvy, enhanced confi dence, vision, and a history of demonstrated achievements.

Phase 4. Declination: characterized by skill degradation or atrophy, loss of confi dence or overconfi dence, stale perspectives, and diminished achievements over time.

These four phases should feel rather intuitive and straightforward to understand. They represent the natural course of performance. Pick any area of life. When these stages are left unattended, they tend to follow along this type of performance trajectory. You learn and improve, grow a little in that area, mature, and become proficient in it until finally you hit an obstacle to improvement as your skills in that area start to degrade and atrophy. On the surface, this seems to be a fated path. But are we merely destined for this sort of performance path?

Well, if we don’t change the trajectory, sure. You will get better and then get worse, and in a hurry. That is, unless you do something to not only change the trajectory but redesign the entire framework. This outcome is not predestined, and you’re not as stuck as it might feel at that moment.

The path forward starts with the decision you made in your Cinderella Moment and opting to enter a phase of renewal instead of resigning yourself to the inevitability of a declination phase. Welcome to the Underdog Curve.

The Underdog Curve

“Burn the boats!” That’s what they say.

That’s what popular wisdom suggests when it comes to attempting anything significant in life. As the thinking goes, the only way to move forward is if you can’t go back—literally or figuratively. Your back must be against the wall. This phrase suggests that humans are not capable of being productive along parallel paths at the same time, as though we’ll lose motivation, energy, or focus if we do multiple things simultaneously.

And while it’s a nice-sounding, albeit hyperbolic, theory, giving up everything is usually not possible for most of us. This is true in every aspect of our lives. If you want to get out of a relationship, you can’t skulk away with your toothbrush in the middle of the night. What about finding a new job or turning a side hustle into a full-fledged business? It’s hard to leave an income behind to venture out into unknown financial territory. The jolt of this pace of change can be overwhelming. Most of us need a more tolerable pace that allows for learning and mistakes, both of which are bound to happen when we do something new.

“Burning the boats” is even less possible for most underdogs. They typically don’t have the support network or resources to accommodate such risky behavior. While this strategy might work well for privileged people with a large safety net, that’s rarely the case for former victims on the path to becoming credible contenders.

Sometimes people confuse the urgency to make the decision to change with the underlying desire to change. It’s fi ne for you to feel the independent pressure to make the initial decision. It’s not acceptable for you to feel like you must give up what you’ve worked for to make future progress. That’s a false dichotomy and not one that will serve you well.

Underdogs require stability to make progress, not the injection of unnecessary tumult and chaos.

Now, you may recall that in the last section we omitted one phase from the Five Phases of Personal Performance—the Renewal phase. The Renewal phase is exactly what it sounds like. Renewal provides an opportunity to enter an adjacent path that allows for refl ection, creativity, and constructive personal development work to be done. It’s a place where you can experiment. Perform some trial and error. Explore and be curious. All of this while you continue to do what you’re doing today, slowly modifying your behavior and activities over time. This is a time for personal preparation and gearing up. But gearing up for what?

Well, remember Vivian from Pretty Woman? At the end of the movie, she decided to pack up her things, move out of the apartment she was living in, and go back to school. Making good decisions related to your personal development is what the Renewal phase is all about. You’re gearing up for change, but intelligently, methodically, and intentionally and at your own pace. 136 The Underdog Curve The Renewal phase is the place to put in work, go back to school, fix your story, develop some new relationships, and figure out how to enhance your performance. Renewal is where you learn to become an authentic underdog. In short, it’s preparing you to leave one trajectory of eventual declination and begin on a new path of development, improvement, and proficiency. In the end, if we desire to avoid inevitable decline, this is the path we must embark on.

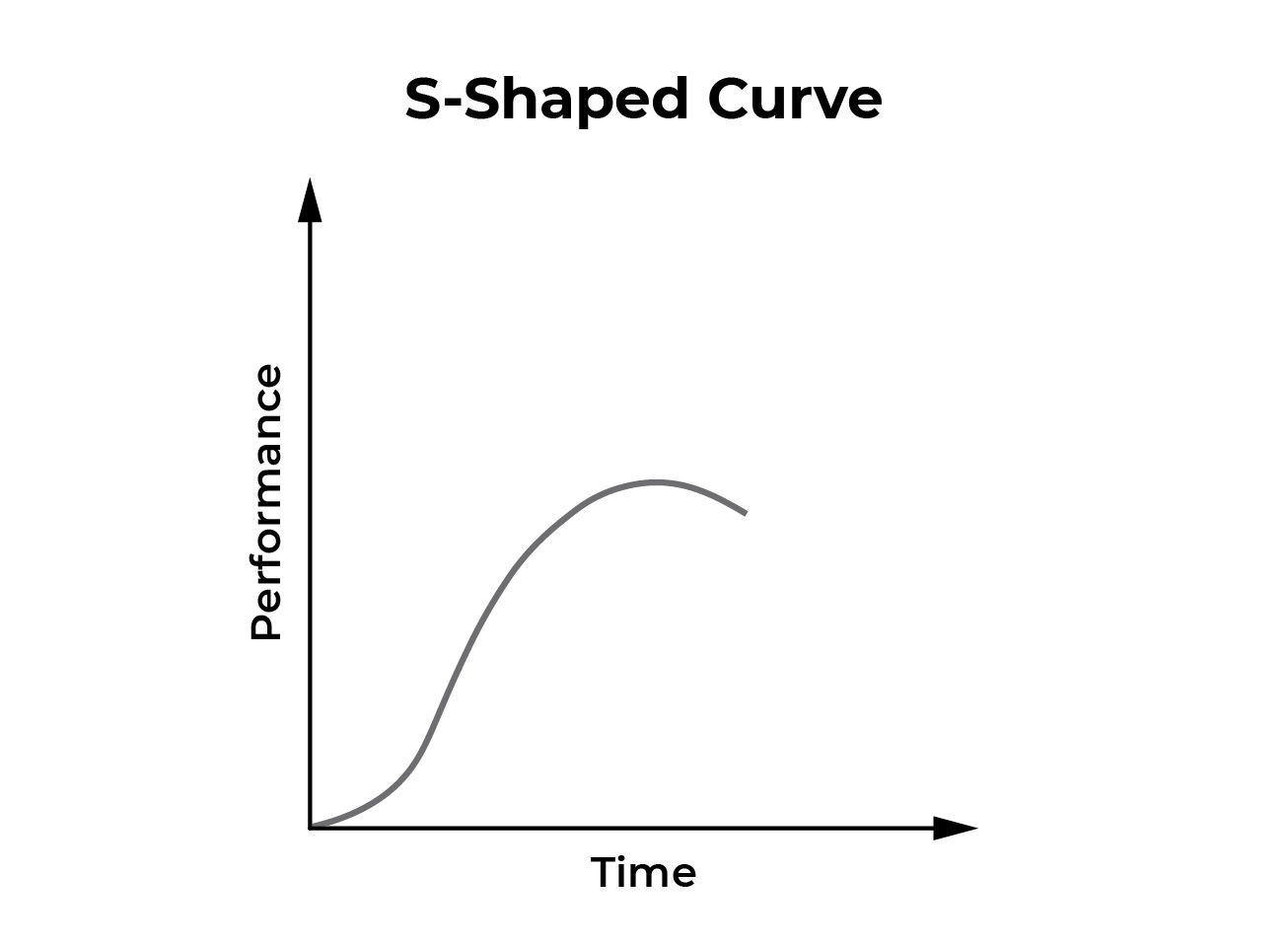

Only now can the Underdog Curve begin to come into focus. The Underdog Curve is a metaphor for how to visualize your personal and professional growth, progress, and evolution. Our curve relies on two components. The first is the mathematical construct known as a sigmoid curve. At its most fundamental element, it is only an “s-shaped curve” on a numbered graph. It looks a little something like figure 8.2:

Notice how the sigmoid curve looks an awful lot like our Fundamental Performance Curve? Well, good eye. That’s exactly what it is: an s-curve with a tail at the point of declination. The other component that the Underdog Curve relies on is work made famous by an author, philosopher, and organizational behaviorist named Charles Handy. Handy reframed the sigmoidal curve to illustrate the basis for change in his book from the 1990s titled The Empty Raincoat. In the book, Handy uses the sigmoidal framework to discuss organizational development and how companies should think about change. Specifically, the metaphorical curve he set up reflects the continuity of change over time in people, operations, or business.41

In his own words, referencing the use of metaphors as tools, Handy suggests, “They are low-definition concepts, imprecise in detail but unexpectedly revealing in the way we look at things.” While metaphors are not purely scientific, they are infinitely helpful to lean on as we work on shifting our performance path. As Handy goes on to explain, “Metaphors are a great aid to understanding, not to be dismissed because they are not strictly scientific.”42

\However, since we’re not particularly concerned with understanding organizational development, let’s modify the curve to fully align with our interests—meaningful underdog development and performance.

The illustration in figure 8.3 shows how the underlying concept works:

The shell of our Underdog Curve reflects two s-curves. The double s-curve visualization is where and how two distinct paths come to intersect and overlap. Let’s examine the rest of the visualization, piece by piece, as we construct the Underdog Curve together.

The first thing to highlight is where the first four phases of our traditional performance curve show up, including Development, Improvement, Proficiency, and Declination. Then we can highlight the Renewal phase. The Renewal phase shows up in the space where the two curves overlap. Visually, figure 8.4 outlines what we have when we put all the parts together:

Now we can see all four phases of the original path, plus the area of overlap called the Renewal phase. You’ll notice that the Renewal phase reflects two trajectories happening at the same time. Handy said, “The sigmoid curve sums up the story of life itself. We start slowly, experimentally, and falteringly; we wax and then we wane.”43 That is, unless we do something about the looming, seemingly inevitable declination phase headed our way. It’s a good thing we can avoid it altogether.

As we put the finishing touches on our curve, there are two additional components to include. The first is where the new trajectory starts or the point where it meets on your current performance curve. Not surprisingly, this is the inflection point known as the Cinderella Moment, which we discussed previously. The second component to include is the The Underdog Curve way back in the introduction—the underdog-specifi c work that will be the primary point of focus during the Renewal phase. As a reminder, the basic equation is refl ected as the following:

Story + Relationships + Performance = Underdog or S + R + P = U

As we add these last two items, the Underdog Curve comes to life, with all its requisite components included. Figure 8.5 provides a visual representation for the completed Underdog Curve:

Next comes the creative and practical work that can only be done in the Renewal phase. Notice that while you’re working on the Underdog Equation, you remain on your original trajectory. Typically, that fi nds you somewhere either in the Improvement or Proficiency phases of your current performance journey. But you could be earlier on the curve, or later. Regardless of where you are now, it’s imperative that you keep doing what you’re doing while you work on making personal improvements in other areas.

As a point of note, the Underdog Curve can be used to think about your life holistically or in segregated areas. Overall, the framework serves to provide a useful metaphor for an overall life trajectory. However, you can also pick any single area of your life and plug it into the framework too. That could be your love life, f inances, career, etc. The Underdog Curve can be used to provide perspective and insights across more discrete areas too; the sky is the limit.

Where you enter the Underdog Curve depends on where you are on your current trajectory when you have the required Cinderella Moment. It may take a while to leave the old curve behind and remain solely on the new one you’re creating concurrently.

One thing that may jump out at you is the length of the Renewal phase—remember, its duration is completely dependent on you. How promptly and diligently are you able to complete the work of the Underdog Equation? Ultimately, you’re in control of both the inflection point and the amount of time it takes to implement the learnings from your new behavior and performance development.

Underdog Competitive Advantage

To be positioned differently, but specifically better, than those around you is to have a competitive advantage. Being different for the sake of it brings little value. Personal competitive advantages 142 The Underdog Curve include things like differentiated performance, being more prepared and better organized, and having access to unique, novel, or creative resources and strong interpersonal networks. The goal of having a competitive advantage is to place you in one or more superior positions to contend with those around you.

Becoming prepared as a credible contender certainly provides you with a competitive advantage over your peers. It also happens to help you avoid the seemingly inevitable declination phase we are all headed for in our personal performance adventure. Our goal should be to try to position ourselves with one or more competitive advantages relative to others as quickly as possible.

There are three important ways you can establish a competitive advantage relative to others around you:

1. Leverage the Underdog Equation—optimize your story, relationships, and performance

2. Internal Underdogging

3. Enacting

As it relates to the Underdog Equation, we will be spending all of part III on the detailed ways you can craft and hone the quality of your story, relationships, and performance. Let’s put a pin in that topic for the time being. Instead, let’s start by examining the idea of “Internal Underdogging.”

In 2018, I did a silly thing. I signed up for a thirty-five-mile ultramarathon. I say silly because I hadn’t run more than a half marathon, and that was only one time. I would like to blame David Goggins for this decision. I randomly came across one of his videos on YouTube, and it got me fired up. He’s a motivational guy, former military special operator, now popular through his social media channels and books. It wasn’t really Goggins’s fault, but he happened to strike the perfect motivational chord with me on the day I signed up. I needed a new challenge, and he provided the right nudge at just the right time. Sometimes timing is everything.

With 105 days until the race, I was feeling more than a little underprepared. However, shortly after I signed up, an interesting thing happened. As soon as the decision was made, at once I started to focus on what would be required next—the training, equipment, and strategy necessary to help me prepare. I needed new running shoes for mountain running. I needed a training plan to map practice runs, a hydration plan, maps of the course and elevations, and a hundred other little details about the race. Within days, I was quickly positioning myself as an ultramarathoner, even though I hadn’t run one yet.

All this preparation was happening unconsciously. It’s only when I reflected in hindsight that I could see the work and planning I put into preparing for the race. While I was doing it, I was focused on the work itself and ignored everything else. Unwittingly, I somehow managed to attract or do exactly the right things to prepare me for the upcoming race. Up until that point, I didn’t even know people were running ultramarathons just down the road from me.

In 2020, Fabien Gargam performed an underdog study to highlight the important aspects that were at play for my decision and planning. While invisible to me at the time, Gargam found that the phenomenon I was experiencing is known as “Internal Underdogging.” This is what it’s called when we adopt certain unconscious behaviors necessary for us to compete and succeed.

In my case, I wasn’t trying to win this race—it was more about trying to finish. During my training, there was another odd thing that happened. When I would tell others about my new goal, many people were confused or unconvinced about why I would attempt something so daunting. Those responses had the effect of running through my mind during my fifteen-to-seventeen-mile practice runs up and around Kennesaw Mountain. They pushed me to train harder. The comments stimulated something within me. As it turns out, Gargam identified this stimulation concept in his work too. He refers to it as “enacting.”44

The idea of enacting refers to a desire to exploit the misconceptions of others while pursuing your vision. Enacting helps us adjust on the fly, like how it gave me strength to get through my practice runs. It also helps you learn the lessons you should from your experiences, see what others have done, and note what’s worked and what hasn’t.

You’ll notice that there is a subtle nuanced difference between enacting and operating with a chip on your shoulder, which we previously discussed. A chip on your shoulder tends to be a defensive response. It’s outward oriented, aimed at proving others wrong. Conversely, enacting is an internal and offensive response. Enacting removes any potential impact of external viewers and focuses on personal accountability instead. It places you in a mindset of wanting to prove yourself right more than proving anyone else wrong. More than that, enacting activates the mentality required for proper preparation.

When we think about doing something challenging or new to us, initially it can feel overwhelming, unmanageable, or even undoable. However, instead of allowing those feelings to prevent us from getting started, we should commit to our goals and fully engage. The process of starting has a miraculous way of bringing into focus both the tools and the preparation required to be successful. As an added benefi t, we can lean on the idea of enacting to tune up our internal mindset about what lies ahead of us.

Now it’s time to circle back to the opportunities available during the Renewal phase and consider how they catalyze unique competitive advantages. To be an underdog, every aspect of your performance must stand out. Up until this point, we’ve used an abbreviated version of the Underdog Equation:

Story + Relationships + Performance = Underdog

As you might have surmised, there’s a little more to it than that. Building on your awareness and learning throughout the book so far, you’re ready to start thinking about the complete equation:

(Two Authentic Stories—Victimhood) + Intentional Relationships + Differentiated Performance = Underdog

The road to differentiation comes down to having two stories, one private and another public. It also requires that you remove all victimhood from them. Then, developing the right kind of new relationships or culling existing ones with intentionality ensures you always have the right people around you. Finally, the biggest way you stand out comes through diff erentiated personal and professional actions or your performance.

There is nothing more advantageous for underdogs than implementing internal underdogging, enacting, and the elements of the Underdog Equation to help you stand out and get ahead. On their own they are powerful, but allowing them to work in tandem is the best way to consistently be viewed as a credible contender. Speaking of updating how we come across to the world—it’s time to begin the work our underdog renewal requires.

Sign up for the only newsletter exclusively for underdogs like you.

Once a week we deliver you one new underdog concept, framework, or insight along with a practial way for you to implement it into your life - for free!