The Underdog Curve

Chapter 6 - How to Recognize Black Swans

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” —Anais Nin

Isn’t It Marvelous?

Marvin Hagler, who would later legally change his name to “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler, started boxing when he was roughly ten years old. He did so at the urging of a social worker. It’s said that at the age of fourteen, he dropped out of school to work in a factory and support his family, and he never looked back. Fortunately, that whole boxing thing worked out for him. Hagler would go on to enjoy a fourteen-year professional career, which landed him in the Boxing Hall of Fame twenty years later.

Marvelous had an impressive professional boxing record of 62-3-2, with an astounding fifty-two of those wins coming by way of knockout. He became the Middleweight Champion of the world in 1980 and successfully defended his title a staggering twelve times between 1980 and 1987 (eleven by knockout).33

Even though Hagler was a World Boxing Champion, he was much lesser known than some of his champion peers. He was standoffish with the media and never landed the big endorsement deals others were getting all around him. The thing about Hagler was that he always did things on his own terms. He quit school when he wanted to. He started his professional career early, taking f ights that only paid him fifty to one hundred dollars per fight.34 Meanwhile, his peers were boxing in the Olympics and landing on the front of Wheaties boxes. On the surface, Hagler acted as though he didn’t mind. He dealt with his frustrations by always trying to prove his worth with his fists.

He took dozens of unnecessary fights with very little income or recognition to show for them. He was winning, slowly, but going about things in the most difficult way possible. Hagler was truculent, literally and figuratively. After he lost his title belt, he never fought again. It was as though he couldn’t bring himself to confront that loss or his own unrealistic expectations.

Hagler was clearly a dark horse in and out of the ring throughout his career. In typical fashion, he epitomized what it means to have a “chip on your shoulder.” It’s a shame because he never got the respect, the big endorsements, or the recognition he deserved, according to the outsized professional success he racked up over the course of a boxing career. The same can be said of many underdogs in their lives and careers.

There are two understandable reasons why underdogs often miss out on or fail to maximize opportunities in life. The first has to do with having that old “chip on your shoulder.” The second reason has to do with an invisible curse.

Both come from a singular source and are enacted in the spirit of autonomy and freedom, when they really only serve to restrain.

Where Do Black Swans Come From?

It seems like a black swan would stand out in a crowd, but our most dangerous adversaries often hide in plain sight.

Nassim Taleb, a professor, author, statistician, and consummate deep thinker, has written several books on the idea of volatility, robustness, anti-fragility, and randomness, among many other topics. In his famous work The Black Swan, Taleb discusses volatility and defines what he refers to as “black swan events.” A black swan event is characterized by a larger-than-usual deviation from the norm. These are events that are so rare or abnormal that the possibility that they could occur is seemingly unforeseeable or unknowable. More importantly, when they do unexpectedly occur, they often have catastrophic impacts.35

Volatility refers to the ability for something to change rapidly and unpredictably, relative to the norm. It’s especially impactful when the change is for the worse.36 Everyone experiences volatility in life. In the normal course of life it is represented by the routine ups and downs of being human. Unpredictability and change seem to sum up life in so many ways. Certainly, not all change is bad, and candidly, ups and downs in life are inevitable and unavoidable. This is routine and normalized volatility and not the worrisome type. The kind of volatility to avoid is the kind we bring upon ourselves. (More on this in a moment.)

For underdogs, volatility is a more visible experience that starts at least as early as your trauma and often continues for many years. However, this type of volatility is asymmetrical, starts with your disadvantage, and continues to disproportionately manifest itself throughout your life. This type of volatility can follow us indefinitely, until we recognize and do something to reign it in. While past volatility may diminish in time, the volatile ramifications of our decisions never truly go away. It’s these large, volatile swings that cause the most pain and heartache for underdogs after they’ve lived through their initial trauma. Underdogs should strive to do everything in their power to avoid new negative volatility swings.

To visualize volatility along our life trajectory, let’s envision life as a simplistic straight line on a graph. On the y-axis, we can place Progress. On the x-axis, we can place Time. In a straight line, that simple graph would look something like figure 6.1.

A helpful way to think about positive versus negative or good versus bad volatility might be to imagine that helpful, positive volatility happens above the line—think marriage, children, or promotion at work. Harmful volatility happens below the line. That might include an illness or a death in the family. Therefore, something like a past disadvantage would be represented by valleys far below the line, while a positive event would be represented by peaks above the line.

Now, when we add in typical, normalized volatility into the chart, the average person’s lifeline might look something like figure 6.2: F

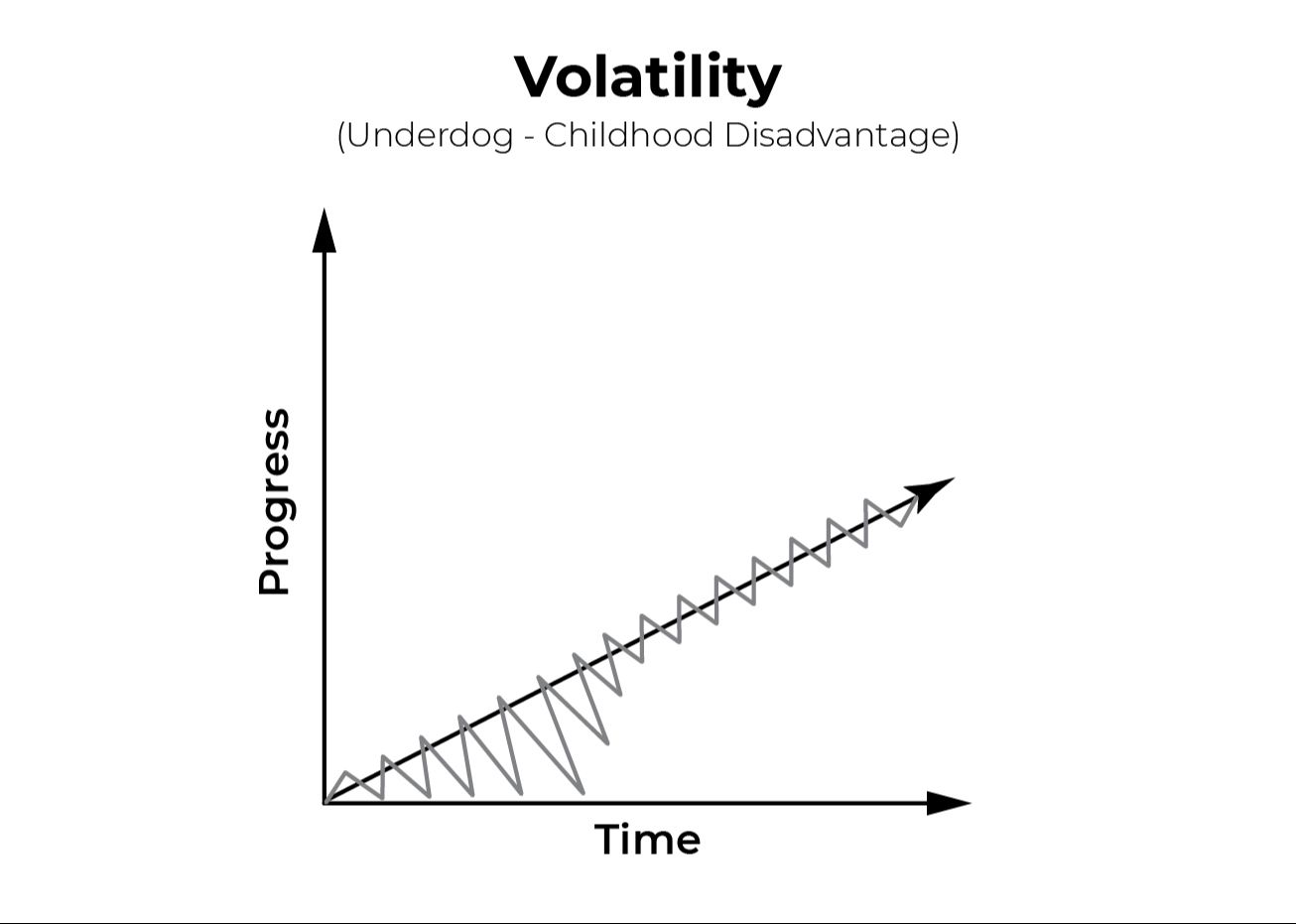

Now we can examine what the volatility of an underdog might look like. It goes without saying that everyone (but especially acute and complex underdogs) would have their own distinct volatility line that’s as unique as their individual experiences. For simple illustration purposes, let’s consider an example where trauma was experienced during childhood and adolescence. If we were to chart that trajectory it might look something like figure 6.3:

Immediately, two things might stand out to you. First, the progress made by the disadvantaged person is represented by a line with an overall lower slope (progress trajectory). Second, the depth of the deepest events below the line. Those are the black swan events, or the unanticipated, highly volatile events of your life. They can be positive or negative. The volatility in and of itself is not inherently good or bad. Rather, it only reflects the degree of effect any single event has on your life, compared to whatever your average volatility is.

Most of us would gladly welcome some positive volatility, like getting an unexpected promotion, getting pregnant after trying for two years, or receiving a fi nancial windfall. These events might occur with less frequency, especially as you start on your journey. Don’t worry, the frequency and likelihood of positive events increases as you grow, recover, and heal during your underdog evolution.

On the negative side, it might be the disadvantage you suffered during childhood, like the example outlined from the last illustration. Or it could be a new disadvantage that shows up. Personally, I’ve had a few. First, there was my ongoing, chronic childhood disadvantage (complex). Then there was the car accident at seventeen (acute). Each would be uniquely represented by their own deep negative volatile swings on my progress trajectory.

The thing about black swan events is that they often show up unexpectedly. That’s especially true when a disadvantage is thrust upon you involuntarily. Other times, these events show up as a function of our own behavior. I alluded to it in the last section.

Underdogs often get caught up in perpetuating two particularly highly volatile or “black swan” behaviors:

1. Walking around with a proverbial “chip on their shoulder.”

2. Getting caught in the “invisible curse” of starting over.

When you’ve experienced a signifi cant disadvantage in life, it has a way of carving certain new pathways in the mind. Over time, those pathways become deeper and deeper ruts, influencing our thoughts, actions, and behaviors. Once you realize you can make it through the most tragic of disadvantages, the everyday demands and difficulties seem mundane or even petty.

Making it through a traumatic event can provide an underlying and sometimes unseen boost in personal confidence. Underdogs should have confidence in spades because of their ability to survive and overcome their difficult experiences. This can be a great quality to have. One should be so lucky as to realize any silver lining from the grip of despair, let alone something this inf initely useful. However, this confidence can become problematic when it serves to set you up to take unnecessary risks.

One of the most valuable underdog skills is the ability to recognize when you’re subjecting yourself to one of these known risks or behaviors. Seeing them coming is a good start, but avoiding them altogether, well, that’s even more productive. Seeing and then reducing knowable, negative volatility is one of the fundamental tenets of being a responsible underdog. Smoothing out your life’s progress trajectory is critical to putting you on an optimal growth and performance path.

Let’s look at both areas more closely to see how and why they show up and what we can do to avoid them before we run into them head on.

That Chip on Your Shoulder Is Showing

When we hear this phrase, we think about someone with a real or imagined grievance about something that happened in the past. They also happen to be looking for an excuse to air that grievance verbally, with their performance behaviors, or in extreme situations through physical aggression. This attitude usually stems from some form of internal fear we harbor—the fear of not fitting in or being found out, the fear of success, the fear of not being good enough, or numerous other variations of the same basal fear.

Today, having a chip on your shoulder is often used to refer to a certain swagger or attitude displayed by stereotypical “underdogs.” The phrase intends to mean someone who is quick to be defensive, who will share the gory details of their trauma, or who otherwise is motivated to visibly prove others wrong. It’s primarily a defensive posture that’s only surface deep. However, by our new definition in chapter 1, this would be how a victim responds, never an underdog.

But underdogs do tend to desire a fair amount of autonomy as they work through their trauma. That freedom includes the desire to prove others wrong, regardless of what it costs and who it hurts, including and especially themselves. It’s not malevolent, per se. It is a byproduct of assuming a certain attitude. However, trying to prove everyone wrong is a poor strategy. Knowing which battles are worth fighting is a big part of underdog success.

Being disadvantaged can partly be held responsible for these types of behaviors. The rest originates from the poor expectations of onlookers who expect underdogs to lose (remember those terrible definitions from chapter 1?). Those expectations are fundamentally about the onlookers and less about the participant. The participant is usually just a proxy for someone else’s agenda. While these ideas may partly explain how underdogs end up with a chip on their shoulder, none of them justify inflicting unnecessary pain on us just to prove someone wrong.

The way underdogs feel about themselves has everything to do with expectations—the ones they have for themselves and the ones placed on them by others. These expectations revolve around what they should, could, and may be capable of doing with their lives. If that’s true, under what conditions are they most likely to be seen as either a credible contender or as a likely loser? Remember, the latter is the better-known expectation.

In 2017, researchers at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania set out to investigate how expectations impact performance. They theorized that underdogs often have an underlying desire to prove others wrong.37

Researchers call this desire to prove others wrong an “interpersonally focused mechanism.” You and I would say this person has a “chip on their shoulder.” This mechanism drives the need to show others that their expectations are wrong about them, and this tactic can sometimes be useful to leverage, but not always. Many underdogs point to defying the odds as a source of motivation to overcome negative circumstances or more chronic disadvantage.

Underdogs often feel a need to push back against expectations to maintain their own sense of personal agency or autonomy. When they feel as though their freedoms are in question, they resist those restraints. The same logic applies to whether the expectations are real or merely perceived. The researchers hypothesized that the disadvantaged would display this form of “psychological reactance” when provided with expectations by others who didn’t meet their own.38

Underdogs are sometimes motivated to perform better when they are perceived to be incapable of performing, competing, or winning by others. In other words, underdogs will buck poor expectations placed on them by outsiders.

However, there is a twist to one of the underlying assumptions in the study. The researchers also suggested that the associated limitation that activates this type of psychological reactance, or that chip-on-your-shoulder mentality, largely depends on who was setting the expectation. They theorized that not all onlookers (“viewers” as they called them) are the same. Therefore, they broke these external viewers into two camps.

The two groups that viewers fall into are either credible or incredible. This credibility is situational and conditional as seen from the underdog’s perspective. Their respective credibility depends on whether the underdog interprets the viewer as having the following three components or characteristics:

1. General trustworthiness

2. Expertise in the topic or performance area in question

3. Relevant information about historical personal performance of the participant

The researchers’ hunch was right. As it turned out, motivation and willingness to try to outperform expectations can be triggered and is performance based, depending on whether the viewer is seen as credible or not. These findings are surprising and supply some interesting context from which to consider our own underdog performance.

Underdogs have a deeper willingness to attempt difficult challenges because we’ve been up against tough things before. On the surface, there’s nothing inherently wrong with trying to outperform expectations and succeed. At least in theory, there’s nothing wrong with this approach, and, when it works, that’s great.

Unfortunately, a lifetime of personal experience suggests that trying to prove everyone wrong has unintended negative effects on us. Living in a constant state of mental conflict is unsustainable. Additionally, it’s impossible to be prepared and win all the time. A better strategy is to be much more selective in which situations and with whom we choose to compete. We also need to consider whether we should or should not regard who is watching. Audience credibility can be the determining factor for whether underdogs exceed performance expectations or not. Strive to engage in settings only when the stakes are valuable and credible viewers exist.

Now let’s consider competing examples between credible and incredible viewers.

When you’re trying to succeed in an area of life where there are incredible viewers watching you, how big are the stakes typically? How much does their opinion or expectation really matter to you or others? Below is a simple example to illustrate the point.

Let’s say you join a club soccer team to play with your same age group. Maybe you’re a little out of shape or overweight, and your team gives you a hard time, not really expecting much from you. If you do not perform or meet their expectations, what’s the worst that can happen? Well, not much, as it turns out. Maybe you get a little embarrassed if you don’t perform better in your league game. On the other side of that coin, what’s the best case if you outperform by scoring two goals and playing great defense? Well, not much besides maybe a pat on the back. It’s a nice short-term feeling, but the impact on your life is relatively low. You proved others wrong, but you don’t get meaningfully rewarded. This is because your teammates don’t know you well, they are at the same skill level as you, and they don’t know anything about your experience with the game.

Alternatively, consider the areas of life where you might meet credible viewers. Perhaps it’s with a romantic interest. Maybe you encounter poor expectations from teachers in school or college. Or as you get older, maybe your work peers or even your boss has low expectations for you professionally. From the research, we identified that it is tougher to beat those expectations because they have the relevant information about you, they are trustworthy, and they have expertise in that respective arena.

Does that mean you should you simply give up and quit? Of course not.

Instead, we should be preparing for these opportunities. In higher-stake pursuits, the competitors will be better equipped, more savvy, and perform at higher levels. The goal then should be to embrace these challenges. To get the most out of any competitive area, you will have to be a credible contender able to compete with those who are advantaged or privileged relative to your experiences and resources.

Underdogs should be targeting the opportunities to exceed expectations only when there are credible viewers. This is where important things like our partners, friends, educational, financial, and job opportunities originate—from contending in more competitive arenas with high stakes and credible viewers present. There are a few items to evaluate as you consider competitive opportunities:

1. Are the stakes sufficiently valuable to engage in this competition?

2. Are the viewers credible?

3. Are you properly prepared to compete with and potentially win against an advantaged opponent who expects you to lose?

If the answer to any one of these questions is no, it’s probably not worth your time to engage. Remember, incredible viewers are not worth the time or energy to try to prove wrong.

To exceed the expectations set by higher-quality competitors and onlookers, proper preparation is vital. As an underdog, this is why our personal performance matters so much (more on this in part III). The story you share, the relationships you develop, and how you ultimately show up conspire to ensure you’re equipped when the stakes truly matter. Being selective in your engagement creates the best opportunities to contend with advantaged individuals and compete for the most desirable things in life.

Opportunities flow to us in direct proportion to our ability to eff ectively manage our attitude, actions, and resulting reputation. This intentional, more strategic, and conscious decision-making mentality is what makes the diff erence in underdog reputation and eventual performance outcomes.

The Invisible Curse

Just because you can do a particular thing, doesn’t mean you necessarily should.

For a long time, I used to say, “You could drop me off in the jungle in South America, in my underwear, and I would likely end up running for president in a couple of years.” And I would tell anyone who would listen. Now, that’s a very hyperbolic statement that is flawed in more ways than I can count. It also sounds egotistical and off-putting to others. (Go ahead, ask me how I know.) It’s presented as a joke and an exaggeration, and I usually used it for my own entertainment. But, as they say, sometimes there’s a morsel of truth in our jokes. While I still stand by the underlying sentiment, I wouldn’t be so naïve as to make this comment in mixed company these days. (You are my people, so I share this with you from a place of humility and slight embarrassment.)

The personal confidence I have to make this type of dramatic claim comes from my experience of having overcome far worse things in life than whatever is in front of me today. The type of confidence that allows you to start over is a unique quality available to those who have endured disadvantage. It’s forged in hardship. It’s only when you’ve overcome real trauma in life that you can muster the willingness and self-confidence to risk everything and start over in one or more areas. Embracing this confidence may be acceptable, but understand that acting on it has real-world consequences.

Until about a decade or so ago, this sort of thinking used to get me into a lot of trouble. I viewed my ability to start over as a tool in my toolbox, at face value, and used that tool a lot. I was willing to start over. That willingness caused me to take outsized risks. I avoided strategizing or planning, and I consistently leaned on this confi dence to start over. And man, have I started over a few times—in school, in romantic relationships, and in my professional life. I’ve been married three times and tried a few diff erent careers, and it took me eight years after I got out of the army to get through college. In 2009, this confi dence left me homeless, again. Yeah, starting over can be a real impediment to progress.

The underlying problem is that I fervently believed in the idea of starting over. I reveled in it, and I was willing to act on it. My willingness to act on that notion caused a lot of unnecessary heartache and turmoil throughout much of my adult life. What it taught me is that my willingness to start over was simply the most extreme manifestation of the binary or all-or-nothing thinking we talked about in chapter 5.

Shall we talk about volatility? Starting over unnecessarily epitomizes the volatility we talked about earlier in this chapter. And the odd thing is, it’s voluntary. We decide to inject this sort of damning, negative black swan event, often with little forethought or planning. Underdogs deserve better.

The Invisible Curse: A willingness to put everything on the line or start over, used as a cop-out or defense mechanism to avoid dealing with the underlying cause of discomfort or challenge in one or more areas of life.

For many, especially when starting out, starting over has its appeal. Here’s the secret that most people won’t tell you: there is no virtue in risking everything just because you can. Speaking from personal experience, risking everything when you absolutely don’t have to is a terrible idea. We can certainly find its rationalization. While starting over may seem like it presents new, fresh opportunities, it’s rarely the action that’s in your best interest.

Sometimes the invisible curse shows up from one dramatic decision. Other times it creeps in insidiously until our hand is forced to move in a particular direction. That creeping develops from apathy or other nihilistic, self-destructive behaviors. We need to remain vigilant of the thoughts, attitudes, and beliefs that can creep in unnoticed.

Often it feels as if we don’t have anything to lose, so starting over seems perfectly acceptable. However, having “nothing” to lose is rarely the case. There is always something that we lose. When you start over, you give up what you’ve worked so hard to earn. That can mean friendships, love, income, or whatever respective outcome you walk away from when you decide to start over. Even when the quality or value of that area in your life seems meager, it’s not nothing. There is an opportunity cost associated with the decision to start over. Like compound interest, the incremental value of the thing you gave up today could have grown significantly for you over time.

Moving on or starting over can be fine. It should, however, be done with extreme care, forethought, and diligence. It’s hard to maintain forward momentum, recover, and heal when you’re always starting over. Momentum leads to progress, which is what we’re after. Speaking of progress, that leads us to our next topic; a single decision that prepares us to get on the Underdog Curve.

Sign up for the only newsletter exclusively for underdogs like you.

Once a week we deliver you one new underdog concept, framework, or insight along with a practial way for you to implement it into your life - for free!