The Underdog Curve

Chapter 4 - Navigating Social Headwinds

Abraham was a young boy growing up in New York City in the early 1900s. His family fled from Russia to avoid religious persecution. They were poor, and his parents were, shall we say, maladjusted. Little Abraham’s family was Jewish at a time when anti-Semitism and ethnic prejudice were reaching a fever pitch internationally. As a kid he was bullied by gangs who would chase him down the street, throwing rocks at him as he ran away. Things were tough for a young Jewish kid navigating the streets of New York.21

At home things weren’t any better. Abraham didn’t get along with his mother very well, whom he viewed as uncaring and narcissistic. Generally, he was neglected and abused by his parents. To avoid the maltreatment, he would withdraw and spend much of his time in the library reading everything he could get his hands on. That’s likely how he figured out that his mother was a narcissist, even though he was only a young boy.

Eventually, this disadvantaged little boy would grow up and gain notoriety. As you may have surmised, this young man’s name was Abraham Maslow. Yes, the same Maslow that famously created what he called the “hierarchy of needs.”22 Surprisingly, we won’t be evaluating or even considering his hierarchy of needs.

Instead, I want to point out a critical misunderstanding that most people make about his work in this area. Psychologists and nonprofessionals alike portray his model as starting at the bottom-most level and progressing up through the five stages sequentially. That interpretation makes the progression from one level to the next depend on the achievement of all the former levels.

While that’s a nice, linear thought experiment, it isn’t accurate. The trouble is that this is not what Maslow intended nor how he wrote about or crafted his hierarchy at all. In actuality, he vehemently claimed the exact opposite—we require, fulfill, and access different parts of the hierarchy often at the same time and in any and all manners of order.23 However, that didn’t stop others from misinterpreting his work and using it to fit their own narrative. A similar phenomenon has been occurring in two distinct areas when it comes to underdogs too.

First, due to an inherent ability to relate to the struggle of the dark horse, many people who are not disadvantaged pursue the use of an underdog narrative for their own benefit. We’ll explore this sense of conflation and their related impacts in the next section.

The second area relates to a general misunderstanding of what it means to be disadvantaged, which we further clarified in chapter 2. Now it’s time to examine the impacts of social misappropriation. But even beyond social misuse like the more recent popularity of “trauma culture,” underdogs themselves struggle with discerning disadvantage from less impactful negative circumstances too. Because of this we’ll introduce a new framework that provides an efficient way to view the events of our lives accurately and objectively.

Let’s start by figuring out why being seen as an underdog seems to be so damn popular.

The Law of Underdog Conflation

The idea of considering yourself an underdog is a personal matter. Until now, each person has created their own definition characterized by their unique experiences. The intent and purpose originate from a deeply personal place within each devotee.

More recently, however, the willingness to be viewed as an underdog, personally or even commercially, has become more popular, and the idea has taken on a life of its own. Many have recognized the value and utility of the construct and the positive exposure it provides in personal and professional settings.

There are good reasons for others to want to get in on the action. First, everyone seems to love a good story of struggle and triumph. It’s natural to want to root for the underprivileged in almost any context. Second, people come to care about and invest time, energy, and resources in supporting those they view as being undeservingly disadvantaged.24 Our desire to help those in need seems to be hardwired into our biochemistry. Third, put simply, these narratives have been shown to draw attention and support across space and time. There seems to be a psychological trigger that pulls on our human instinct to support those in need around us. It works by tapping into a level of engagement not attainable with most other stories, narratives, personalities, or archetypes.

The challenge for those who have really been through diffi cult events is that the use of specious narratives by others can have the eff ect of making you question the utility, value, or even the validity of your own story. This is a troubling reality, which has led to the development of the Law of Underdog Confl ation to explain how and why this happens so frequently. Our new law includes three principles which are outlined as follows:

1. The Principle of Universal Relatability

2. The Co-opt Principle

3. The Temporal Principle

These three principles help explain how and why the underdog construct has come to be so popular and socially misunderstood. Viewed through this lens, subjective adversity and the desire for support can become easily confused with real adversity and the need for support. These are not equal pursuits. To take this idea one step further, it’s easy to see how there may be some less scrupulous individuals willing to leverage unwarranted support to their own benefi t.

At first blush, you may notice that these rules may seem almost paradoxical in nature or even contradict the entire underdog construct. However, I assure you they are wholly real and worth better understanding. Recognizing these when they show up serves to help you better position your own story among the more questionable narratives you’ll run into.

Developing a better understanding of the headwinds you face as an underdog is akin to becoming more aerodynamic in their presence. While recognizing the aspects of the Law of Social Conf lation won’t prevent their existence, it can mitigate the impact they have on you personally. It will help you tolerate their presence with poise and clarity.

It’s important to keep in mind the influence and effect these social conventions have on viewers too—a.k.a. everyone with whom underdogs interact. In essence, these principles influence how others view them. The way others project onto and use the underdog narrative affects the behaviors and attitudes of those watching. All of this can have a cooling effect on authentic stories of adversity.

My own experience suggests that people generally fall into two broad camps when it comes to supporting underdogs: antagonists or advocates.

There are those who perceive underdogs as merely losers or victims. They’re the ones who have negative visceral reactions when the concept is brought up. I’m reminded of an experience I had in a writing workshop a few years ago. I introduced this book idea in a small group setting, when one of the participants started laughing and said, “Whoa! Who wants to read a book about losers?” In my experience this is a rather typical response of the privileged.

At best, these folks respond with a sense of apathy. Often, however, they react and engage with disdain or condescension, neither of which is helpful to underdogs. Let’s refer to this camp as the antagonists.

In contrast, there are those among us who revere underdogs, f inding inspiration in their story, and are kinetically poised to support and advocate for them. They engage with them with genuine curiosity and a sense of wonder. This group can recognize and evaluate the disadvantages and difficulties endured by each individual. As a result, their reaction is demonstrated through empathy and attunement. Let’s refer to this camp as the advocates.

As you might imagine, underdogs want to focus on avoiding the former and engaging with the latter; everyone who has been through struggle and strife in life can use a few more advocates in their corner.

Now, let’s consider each principle and its impact on you in more detail.

The Principle of Universal Relatability

Universal relatability is the most fundamental of the three principles and the one upon which all others are built.

It simply means that we can all inherently relate to the feeling or idea of being an underdog. This goes for all of us regardless of whether we have experienced any real difficulties or not. The ability to tap into the associated emotion and even the mindset is naturally occurring in us all. Obviously, however, empathizing with this narrative and having experienced real disadvantage are two very different things. Fortunately, for most who have never been disadvantaged, considering themselves an underdog never crosses their mind.

This cuts two different ways. It can be helpful that others around you can relate to what you’ve been through, even when they don’t have first-hand experience with your specific trauma. Empathy is a valuable emotion and a helpful starting point for relationship development. Conversely, there is a more detrimental use employed by a subset of less scrupulous, or perhaps exceedingly unaware, folks looking to get ahead by any means possible.

This brings us to our next area of focus: The Co-opt Principle.

The Co-opt Principle

With enough mental gymnastics, almost anyone’s story could be contorted to fi t a specious narrative. Lately it seems as though everyone wants to fall into the underdog category.

There’s power in being labeled an underdog by credible people. That fact has not gone unnoticed by the masses. As a result, a sense of competition has developed for this coveted stigma recognition. Scientists refer to this as “jockeying for stigma.”25 In short, some people with no perceptible disadvantage co-opt the underdog narrative only for the perceived benefi ts.

Which brings us to the idea of the Underdog Co-opt Principle. It’s an important reality to understand, as it is happening all around us in personal, professional, and business settings. It’s something to be aware of so the underprivileged can adapt their authentic story to readily stand out. You’ve probably noticed throughout the book I use words like real, authentic, or actual to delineate between real and fake underdog narratives. This isn’t by accident.

It’s time to put a name to these two diff erent narrative categories.

Authentic Underdog Narrative: A true story of disadvantage, including an empowered private story or an inspirational public story told by someone who has either overcome or is actively working to overcome their personal disadvantage.

Pseudo-Underdog Narrative: A false, disingenuous, or superf i cial narrative of relative or contextual disadvantage, often based on partial, selective, or circumstantial evidence, used to manipulate or evoke an emotional response, support, or advocacy from individuals or customers solely for personal or professional gain.

Using the newly defined words authentic or pseudo underdog serves two purposes for us going forward. First, we now have a common language to reference so we can quickly draw the proper distinctions as we consider them throughout this book. Second, and more importantly, you can now use this as a lens through which to view the stories you encounter in your day-to-day life.

The Temporal Principle

“One can only be an underdog before a competition takes place. Afterward, you are either a winner or a loser.”26

There is an incredibly odd space that the disadvantaged eventually occupy once they achieve success in any area. There’s a dissonance between how it feels to be newly successful and also still feel like an underdog. One moment you’re just one of many competitors whom no one recognizes or believes in. You’re merely an underdog and expected to lose.

Then, to the surprise and wonder of everyone around, you earn a big promotion at work, you marry your dream partner, or your business starts to take off and succeed. Suddenly, you’re an “overnight success.” Yesterday you were an underdog; today you’re a champion. Well, which one is it? The feeling this leaves you with can be jarring.

How is it that you can flip from being viewed as expected to lose to being viewed as a champion with the snap of your fingers? This is what I call the Temporal Underdog Principle. Underdogs seemingly exist in an everlasting, temporal state of success or failure purgatory. But remember, this relates only to how others perceive you, not how you identify internally.

Underdogs are most readily recognized only when they are expected to lose, they are powerless, or they are perceived as such. They are far less likely to be viewed in the same way once they show any visible degree of success. In essence, you can only be an underdog before a competition takes place.27

Does this simply mean you’re no longer an underdog as soon as you experience any degree of success? Has your story or struggle changed? Have your disadvantages suddenly disappeared because you achieved something worthwhile? Are you now cured of all that ails you because you happened to win on a given front? Of course not, but underdogs need to know how to contend with the f leeting nature of how they’re perceived by others.

Your circumstances may have changed, but what hasn’t changed is your history, where you came from, or your struggles. For you, these are all still very real. For others, these may become more difficult to see now. Obviously, your own story and personal narrative are things that stay with you, even though, on the surface and to everyone watching, most people only see your newfound success. They quickly lose appreciation for what you’ve endured to get there.

You will need to be aware of this phenomenon happening around you. It will require that your story is that much more clear, compelling, and inspiring if you hope to continue to earn support from those who desire to advocate for you.

In summary, here are a few key ideas to keep in mind when it comes to the Temporal Underdog Principle:

• Perception reigns. The temporal aspect of being seen as an underdog makes it difficult to support you after you’ve “won.”

• Share your story. Having an ongoing underdog narrative to share with others helps you appropriately contextualize who you are and what you’re working through.

• Develop Advocacy. Underdogs don’t need the support of everyone, only a few consistent advocates and an ability to develop more throughout their life as needed. (More on this topic in chapter 11.)

Privately, you know the struggles you’ve been through and still feel the same way you did before the event, even after you’ve won. You feel like an underdog because you still are one. Remember that winning doesn’t take away your underdog nature, history, struggle, disadvantage, or trauma, and it certainly doesn’t take away your story. It only serves to enhance it, make it fuller, and supply a larger platform from which to deliver your story to more people, creating an opportunity to make an even bigger impact. Think back on the examples we used of The Hunger Games character Katniss, or of Simone Biles’ achievements. Your success has come despite what you have endured. These feelings should propel you to greater heights, keeping you sharp and focused on the future opportunities that lie before you.

Eventually you may not rely on the same story you once told, but no one and nothing can take away the experiences you’ve had and the difficulties you’ve overcome while you pursued success.

Circumstance vs. Disadvantage

Over the last few decades, we’ve witnessed a slow conflation of an unfavorable circumstance and an objective disadvantage. Colloquially, we often interchange how we use these concepts. Practically, these two ideas have very different impacts on our lives. Distinguishing between them is a very helpful skill, especially for those dealing with challenges on both sides of this fence.

Let’s start by considering what an unfavorable circumstance is. Take the loss of a job, for example. An involuntary job loss can be an impactful event in our lives, causing temporary emotional, f inancial, and especially psychological distress. Ultimately, however, this is a circumstance that is readily surmountable in most instances. With some effort we can dust off our resume, engage in the job market, and find a new opportunity within a few weeks or months, assuming we are able and willing to reengage. While often shocking at first, it can be overcome and often comes with unanticipated upsides like some needed time away, a more fulfilling or higher paying job, or a better company culture.

Disadvantages are different. As we discussed back in chapter 2, disadvantages come in two varieties: voluntary and involuntary. When it comes to authentic underdogs, we’re concerned with the latter—involuntary. These types of traumatic, disadvantageous events tend to have a lasting impact in major areas of our lives, like our family, economics, social status, or physical or psychological well-being. These are not readily surmountable in the short term and often require therapy and the help and support of others.

My aim is not to name or classify every type of disadvantage you may have suffered. You know it when you see it, or likely when you experienced it. Disadvantages are tricky. You’ve probably had the experience in your own life of them tending to cross over the boundaries of different categories. It’s not cut and dry, hard and fast, black or white. One type of disadvantage can begin in a single area and spread across other areas of our life quickly. Below are a few examples of how disadvantage affects us in numerous ways, beginning from a single source:

• Poverty is not only an economic issue but also a social and psychological one.

• Sexual abuse is not only a sexual/physical trauma but also a psychological one.

• Physical abuse also has familial and social impacts and psychological effects.

It should be self-evident by now that disadvantages are complicated and messy. They spill over into one another. Being affected in one way is often less about the initial event and more about the longer-term ramifications, pain, or shame associated with the original trauma. Our feelings about one event or a series of events linger with us throughout life. It’s these lingering feelings that can drive and motivate us to overcome these experiences over time.

In this case, what is the value of understanding the nuances of circumstances and disadvantages?

Easy. If we’re not careful, we can begin to equate all the unfavorable circumstances of our lives—likening minor, surmountable circumstances with far more impactful disadvantages. This is the risk of the underdog. When you’re already reeling from difficulty or trauma and then get hit with a surmountable but negative circumstance, it can be easy to mix-up the two kinds of disparate negative events in our minds.

Confusing these two only serves to prevent us from overcoming circumstances as quickly as we should. In the long term, treating these events equally can exacerbate older trauma, making it more difficult to heal. The added side effect is that it can skew your story, making it sound unnecessarily negative, or cause you to come off as unaware, cynical, or even a victim.

The ability to effectively distinguish between the two ideas has far-reaching positive effects for underdogs on the mend.

The Law of Disadvantage

The events of our lives can be broken down into three distinct categories: favorable, neutral, or unfavorable. Establishing these three primary categories can help us draw the proper distinction between the unique ways in which each may affect us. The naming of these three groups should seem rather self-explanatory.

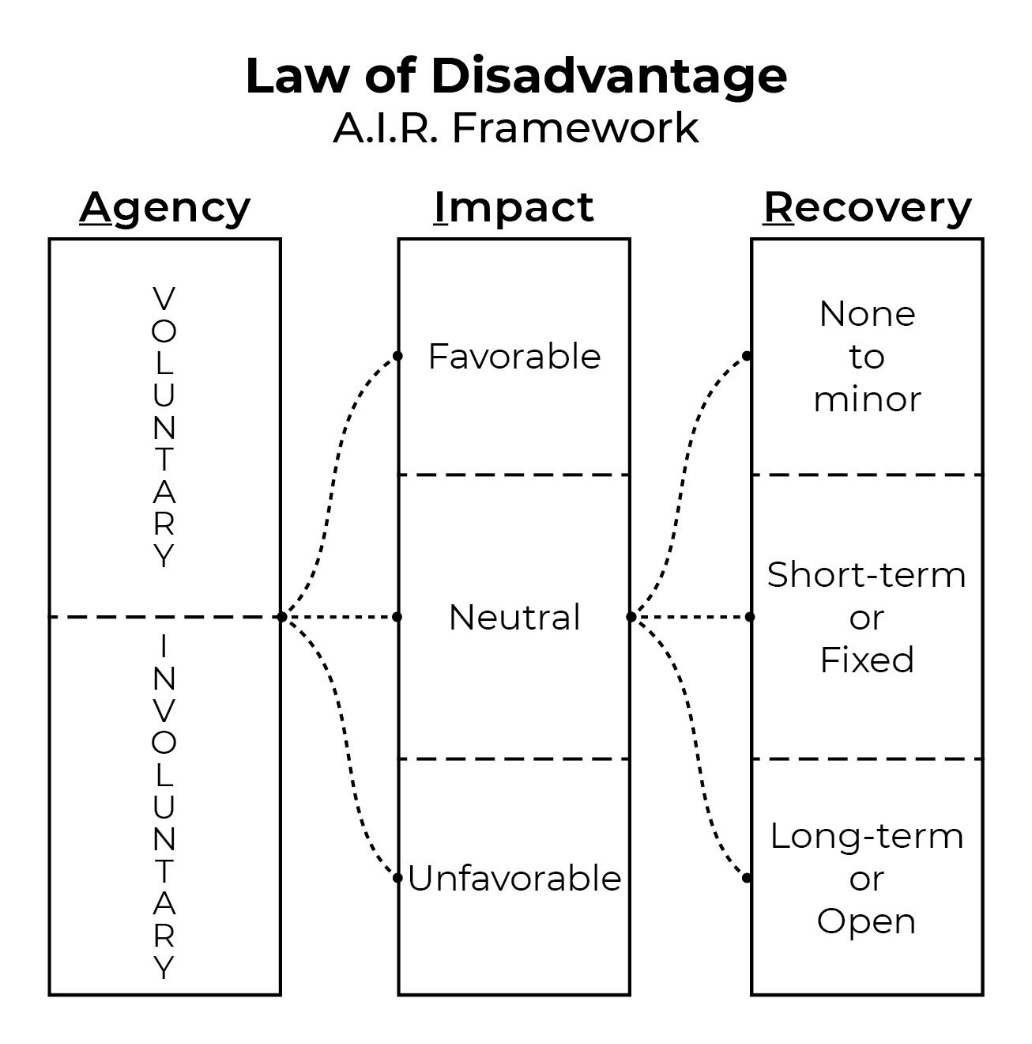

What’s less clear is why different circumstances seem to affect us to varying degrees. That’s where the Law of Disadvantage (LOD) comes in. The LOD is designed to break down any event into its appropriate context, filtering it into three essential evaluation areas: agency, impact, and recovery (AIR). Once you have a handle on how to use the AIR framework, you will be able to distinguish between more superficial negative circumstances and more significant disadvantage quickly and effectively.

Regardless of whether something positive, neutral, or negative happens to us or for us, the model provides objectivity and clarity to help you differentiate between the profundity of any of life’s circumstances. The operative word here being objectivity.

The first area to consider is agency. Agency dictates whether an event was chosen by us or whether the circumstance was thrust upon us by someone or something else. It answers the following question: Was the experience voluntary or involuntary?

The second area relates to impact. This aspect has to do with the depth of the effect a life event has on us. Broadly, it outlines whether an event provides a favorable, neutral, or unfavorable effect in our lives. Not all events are favorable or unfavorable, thus the need for a neutral category.

The third and final aspect involved is recovery. There are two associated dimensions, including the amount of time and level of intensity needed to recover from the event. This involves a range— from zero time and minor effort to fixed time and minor effort to more extensive recoveries requiring an open timeline and longer-term recovery. This should help you clarify the difficulty of the recovery needed to conquer any life event.

The goal of the model is to help provide you with context and clarity for the events of your life. As we mentioned earlier, sometimes when we are in the middle of dealing with something diffi cult, it’s hard to objectively view the occurrence. The more profound or diffi cult something is for us to manage, the harder it can be to accurately see things. The LOD model is useful to help with this.

For each situation we encounter in life, we have a decision to make about how we respond to it. This includes situations and circumstances that happen to us in the present and in the past. Objectivity is important. And just because we may have a history of viewing a past event in our life one way, it doesn’t mean we can’t change our mind and take a diff erent view. True healing has a way of improving our perception and shifting our perspective about events. Changing our minds and updating our views is allowed and encouraged. In fact, the ability to change our mind is an essential part of our maturity, personal development, and recovery.

In using the AIR framework, from the agency, impact, and recovery categories, consider the details of the experience and pick one of the available options in each group to provide you context for the situation in question. You will fi nd that there are numerous combinations. Here’s a simple breakdown for how to use the model shown in Figure 4.1 to view any circumstance in your life:

• Step #1. In agency, fi gure out if you initiated the experience (voluntary) or whether someone or something else imposed the circumstance on you (involuntary).

• Step #2. Next, in impact, select whether the circumstance is favorable, neutral, or unfavorable.

• Step #3. Finally, fi gure out the predicted level of time and intensity that might be needed for your recovery, if applicable: minor/none, fi xed/short term, or open/long term.

As you consider the model, you will find that several possible scenarios exist using the three primary variables. When you run most events through the LOD model, you end up finding that many of them are readily surmountable either with a shift in attitude about the event or with a little work on your part. Now let’s consider a few possible impact areas to get the hang of how to use the framework.

Favorable circumstances are simply that: beneficial to you. Whether you or someone else is responsible, who cares? Take the win. Not much to do here but to enjoy and celebrate. It might also help to contemplate the actions that led to this favorable event. This might be something like an unexpected promotion at work or your wife sharing the news that she’s finally pregnant after a year of trying to conceive. This is the good side of life; celebrate and treasure these moments.

Neutral circumstances are neither good nor bad, per se. Therefore, they should have limited impact on you, regardless of whether the circumstance is voluntary or involuntary. Your recovery should be minor or such that it isn’t going to negatively affect you. Imagine you get a new neighbor next door or your brother tells you that you’re going to be an aunt or uncle soon. These events don’t have much impact on your life from a day-to-day perspective.

Then there are routine unfavorable circumstances. We mentioned one such event earlier when we talked about a job loss. That would certainly be unfavorable. It might also fall into the category of being involuntary if you were terminated or laid off, but the depth of your recovery is an important consideration for these types of events. While you may suffer some short-term psychological impact from the incident, a proactive response would place this event squarely in the “fixed” recovery area. You are in control over your response, and you determine how long it will take you to bounce back. As we mentioned earlier, objectivity and clarity help you avoid falling into the trap of self-victimization with the more ordinary, manageable events of our lives.

On occasion, you will find one combination within the model that is a more significant event. This involves the more profound idea of disadvantage. Surely, a disadvantage would need to fall into the involuntary category. It must be something that you have no control over. It is thrust upon you by someone or something outside your control.

A disadvantage would also fit squarely into the unfavorable impact category. Beyond that, the circumstance must also fall into the open recovery category, requiring significant time and energy to fully recover. The full depth of recovery may be unknown and even require some outside help.

Underdog Disadvantage (acute/complex) must be objectively involuntary, provide an unfavorable impact, and require an open level of recovery.

Involuntary, unfavorable, and open is the only combination in the model that can be defined as a true disadvantage. The ability to recognize the distinction is a powerful skill to have access to. You can think of this new technique as a kind of personal awareness, and that’s a powerful tool in your toolbelt. It’s sort of like a tape measure: it may not be the only tool you need, but you will find that most jobs can’t be completed without it.

There’s a well-known parable that comes to mind about a fish in water. There are these two young fish swimming along one day, and they run into an older fish swimming in the opposite direction. He nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” The other two fi sh swim on for a while, until one of them eventually turns to the other and asks, “What the hell is water?”28

It’s difficult to perform at peak levels when you don’t know how to appropriately characterize and respond to the events that life throws at you. Circumstantial and disadvantageous events in your life are distinct—respond accordingly.

Sign up for the only newsletter exclusively for underdogs like you.

Once a week we deliver you one new underdog concept, framework, or insight along with a practial way for you to implement it into your life - for free!