The Underdog Curve

Chapter 3 - The Science of Underdog Distinction

What do a homeless man, an embattled former US president, Paris Hilton, and Rocky Balboa all have in common?

In 2010, a group of researchers from Harvard University, Boston College, and Simmons University got together to conduct a series of ambitious experiments to probe this fundamental idea. Candidly, the team didn’t set out to revolutionize the underdog construct. Instead, they were focused only on a single area in the business world related to consumer reaction to brand biographies. Fortunately for us, they got a little more than they bargained for when they performed the research they called the “Underdog Effect.”20

Leading up to their research, the group noticed an emerging trend. Increasingly, businesses were positioning themselves as having overcome perceived disadvantage in their branding and marketing campaigns. They noticed that not all these companies could possibly have real dark-horse stories. The presumption was that firms must adopt these types of stories because they resonate more deeply with customers, thereby influencing their future purchase intentions. Beyond consumer intentions, the researchers were interested in understanding how customers feel about brands that shared an underdog origin story—real or embellished.

Leveraging additional primary research on brand identity, self-congruity, and brand attitudes, the team came up with the following theories:

1. Consumers will show higher brand preference and purchase intentions for brands with an underdog biography.

2. Increased preference and purchase intentions for brands with underdog biographies will be mediated by consumer identification with the brand.

3. The more consumers self-identify as underdogs, the more likely it is that they will prefer brands with a similar brand biography.

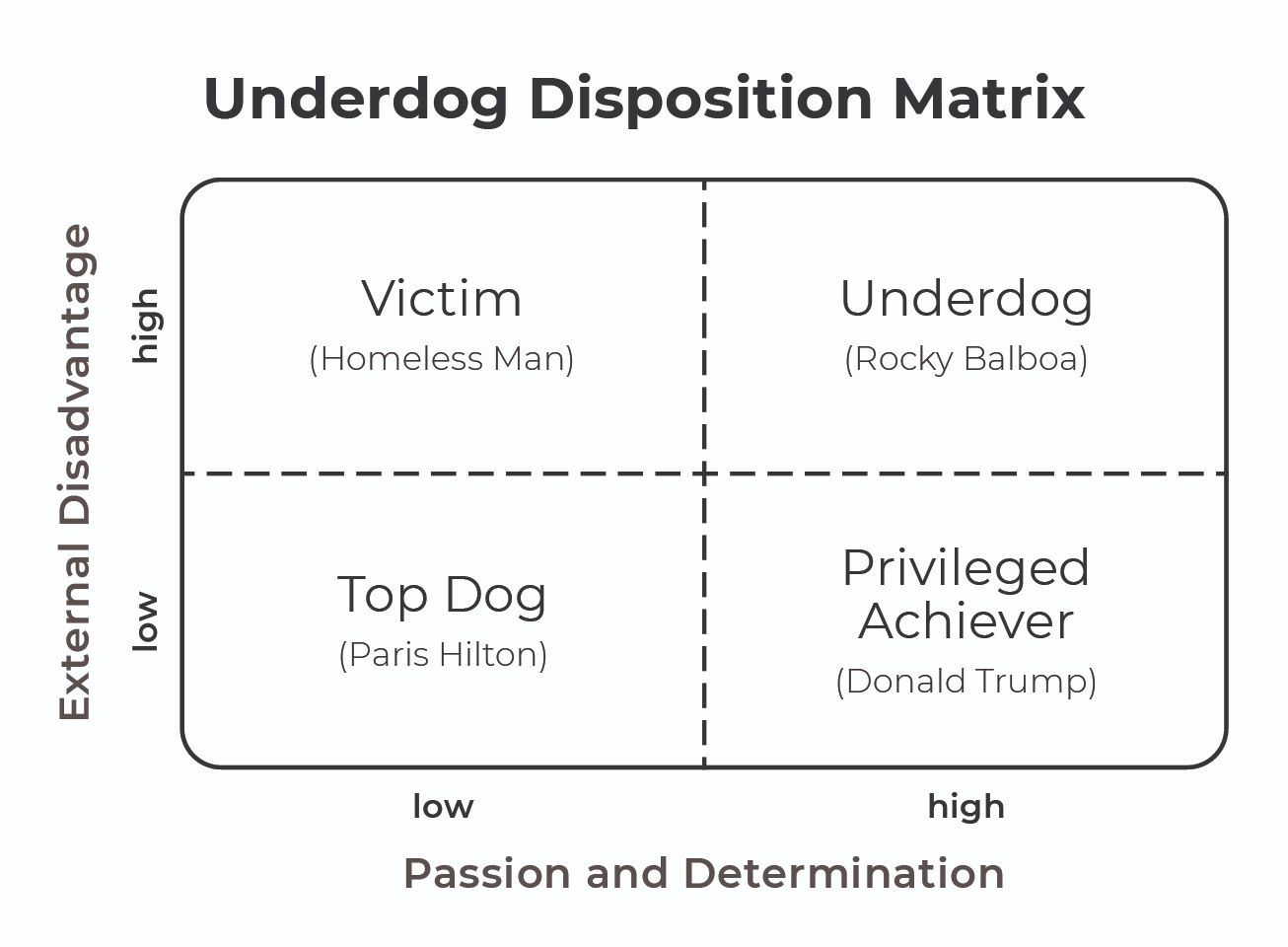

And remember our four characters from the beginning of the chapter: a homeless man, Paris Hilton, Rocky Balboa, and a former US president. They used each character as an avatar for their four predicted “brand biography” groups into which people could be easily categorized. As expected, when tested, participants were readily able to place each character into their predefined “brand biography” classification.

In figure 3.1 you can see their four classifications and where each character was placed by researchers.

There are several important findings that came from their work on “brand biographies.”

1. First, the naming convention classifications used for their personas—victim, underdog, top dog, and privileged achiever.

2. Second, the fact that study participants were able to accurately predict which group to place each character into based on the written prompt from the study.

Broadly, I believe their findings support the accurate universal recognition of underdog narratives and our innate ability to appropriately see where others are in the world relative to their lots in life. Moreover, this is the first time that these terms were both used and provided with context and definition. This was a huge leap forward for the cause. We will discuss each in more detail later in this chapter and lean on these terms throughout the book to refer to certain personas or avatars.

The most astounding fi nding that came from the team’s research had to do with the areas that people most agree establish an underdog in the fi rst place. There are two essential areas that stood out among the hundreds of participants surveyed:

1. External Disadvantage (ED). The nature of having to overcome some degree of external disadvantage, defi ned as “high obstacles and few resources.”

2. Passion and Determination (P&D). This dimension is two-fold, identifi ed as a combination of two correlated concepts: passion and determination. Supporting characteristics include resilience and perseverance.

Beyond naming classifi cations and essential characteristics, what else did the team’s results highlight? In each study across these distinct personas, the results pointed to a strong preference for the underdog story over those of top dogs, of privileged achievers, and especially of victims.

This is a central point to note: people have a strong preference for and are drawn toward these stories, preferring underdog stories especially when there are competing narratives from which to choose. And in life there are always competing narratives.

This is one of the things that make underdogs so compelling and so human. We all have an inborn orientation to support those whom we perceive to be at a disadvantage. In other words, it’s human to want to support those who’ve endured adversity— and that’s a good and virtuous thing.

At this point you might be saying to yourself, “That’s great, George, but what’s a research study got to do with me?” As it turns out, quite a lot, especially if you’ve ever experienced disadvantage and if you see value in viewing yourself as an underdog.

In one short series of studies, this team inadvertently flipped what we know about underdogs on its head. Their work cemented a serious new vernacular for how to classify people broadly (top dogs, privileged achievers, underdogs, or victims). They also provided a baseline of necessary requirements to be considered one, which includes folks who are externally disadvantaged and who also demonstrate passion and determination.

Now, frankly, they were primarily concerned about how these behaviors show up from a consumer preference standpoint. You and I may not be particularly interested in developing a marketing strategy, per se, but what the researchers were really studying is human behavioral preferences to a set stimulus; in this case that stimulus was an underdog story. That’s something we care a great deal about. Considering the research team’s methods and rigor, we can make a reasonable logical leap to suggest that if humans feel this strongly toward these types of stories when simply comparing commercial brands, surely those same feelings and preferences manifest in the way we respond to similar stories in a personal or professional setting too.

External Stimulus, Internal Response

As we saw in the last section, we all have an ability to recognize disadvantage when we see it. You will recall the two things that an underdog has are both external disadvantage and passion/determination.

But these alone are only table stakes, as they say. You can’t be an underdog without both components present. There are other supporting attributes, but these two fundamental factors are required. There is something hidden in plain sight within these two concepts. In a weird way, these two ideas are complements to one another.

A disadvantage is a trigger that victimizes us or happens to us. Disadvantages, in all but contextual scenarios, are events or series of events that happen involuntarily. They are typically thrust upon us, with our having little to no control over how or when they show up.

Passion and determination are a one-two combination that make up a response mechanism, which burns from within. These innate characteristics show up in individuals after they’ve been disadvantaged. They are nuanced in their depth. The specific triggers inside each of us differ, and their effective use requires practice as they have a steep learning curve. When these two don’t show up, we call those folks victims, which we’ll come back to shortly.

This is not to say that only the disadvantaged among us can show passion and determination, but it happens to be the case that underdogs are the only group of people who meet both parts of the requirements—disadvantage and passion/determination. If you only have passion and determination with no disadvantage, that simply leaves you neutral, advantaged, or privileged in life—a great starting position for anyone.

It can be helpful to think about these two ideas as an external trigger and an internal response.

• Disadvantage: A stimulus that happens to us from an external source.

• Passion/determination: A set of internal personal responses to disadvantage.

The external negative stimulus creates the conditions necessary for an internal response. The behavior can show up in various forms; it is merely an opportunity. If you recall from chapter one, not everyone reacts in the same way. For example, “losers” respond with avoidance. They shut down and become victims or martyrs by choice. Underdogs, on the other hand, lean in and engage. Disadvantage prompts a response deep inside of them. They’re motivated by their adversity with something igniting a deep yearning to overcome this thing that has been cast upon them without their consent.

Passion is another word to describe a sort of intense enthusiasm, but more than that, passion fl irts with the idea of suff ering and sacrifi ce. It’s why we talk about suff ering for our art or the thing we love. We suff er in our passion for someone or something. A single spark can ignite the flames of passion, giving us the energy to rectify the wrongs of the past and build a better life for ourselves. Passion burns hot and can help us improve, overcome, or surmount obstacles, but it can also have a short life span. It burns intensely but can flame out quickly when not stoked or refueled. It may get relit with a simple reminder but may be left simmering. This is where determination comes in to reinforce the intensity.

Determination is all about purpose. It’s a deep-seated resolve that comes from the depths of one’s being. Determination is a resolute decision to do something that matters to us. Then, it shows up as the habits, goals, and will power that keep the fire or passion going to pursue the things that matter to us.

The ability to both become and sustain being an underdog begins with acknowledging your disadvantage and stimulating the fires of internal passion and determination. Most of us are going to need all the help we can get to work through our disadvantages and avoid remaining a victim.

Now that we know what underdogs are made of and where they come from, let’s compare them to everyone else and see how they fit in.

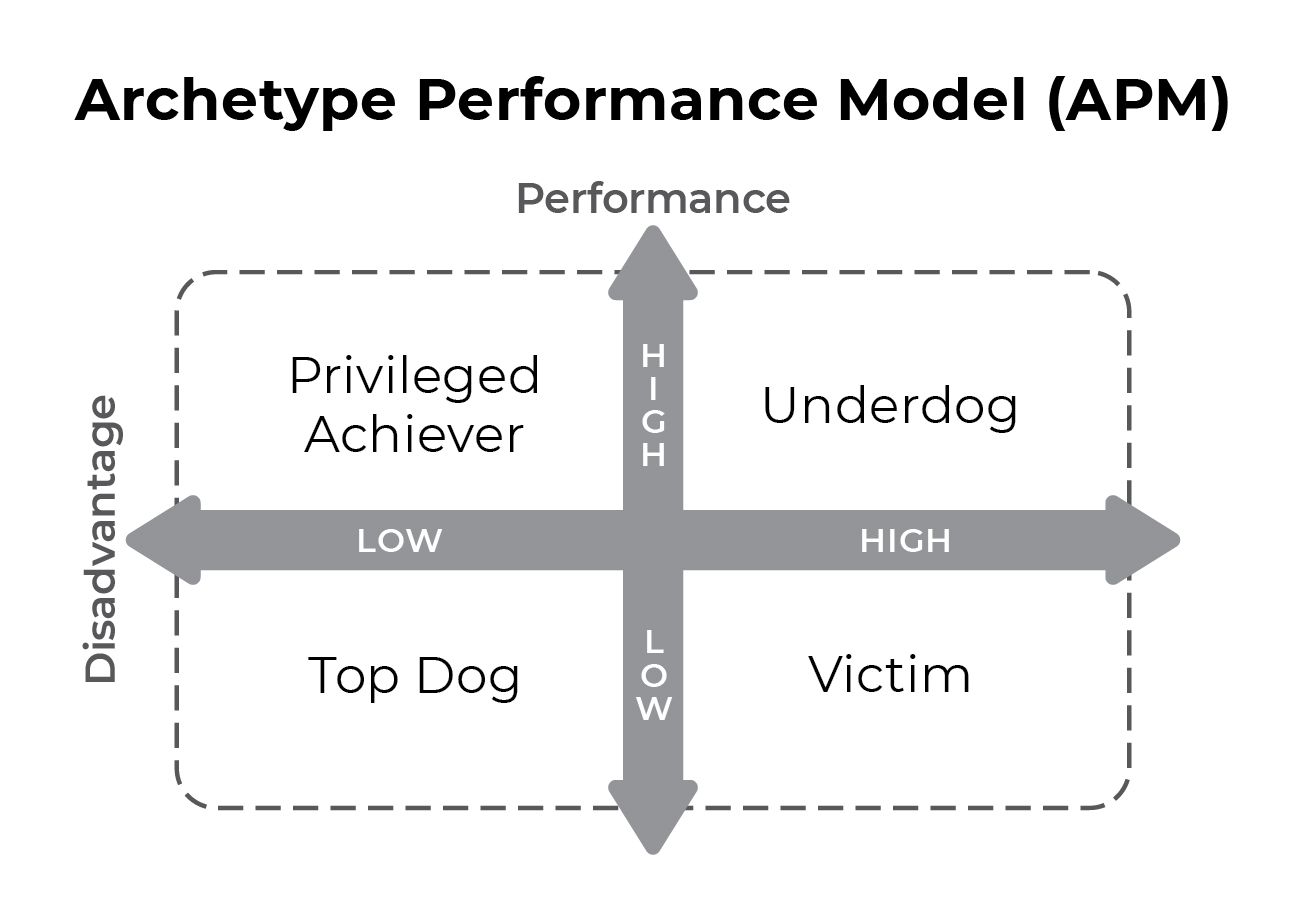

The Archetype Performance Model (APM)

Earlier in the chapter, we concluded each of us can be sorted into one of four broad categories: victims, privileged achievers, top dogs, or underdogs. Limiting our discussion to a few groups and keeping our model simple will improve the comparative context and drive home what makes each group distinguishable from one another.

In common social vernacular today, there is some confusion about the names and definitions associated with each archetype or classification. By way of example, in the conventional metaphor, top dogs are often confused as being the opposite of underdogs. They seem to be the thing to aspire to—a winner instead of a loser in the more literal sense, goes the thinking. While this seems to make intuitive sense, you’ll see in a moment that top dogs have very little to do with underdogs once we break down the interplay between each classification.

Like most things in life, a simple binary construct of only winners or losers removes the nuance necessary to see underdogs in the appropriate light. Winning and losing can be deceptive when isolated and viewed in the context of a single competition or life event. However, when winning or losing are viewed across many events over time, the outcome trajectory comes into focus and the results become more observable. The broader view allows us to see the proportion of wins and losses and make more appropriate performance characterizations.

No one person, group, or team can win every time. To use a baseball metaphor, consider that a player can strike out or fail to get on base 70 percent of the time and still have a Hall of Fame career. A mere 30 percent success rate is more than sufficient for them to be considered among the most successful in the sport. If we viewed someone’s strike out only once and judged their performance on this single instance, we would be missing the broader view of their overall performance over time.

Therefore, to distinguish between groups, it’s helpful to establish a framework that contrasts the archetypes from one another. Any framework we consider needs to clarify and outline the interplay between the groups. That includes understanding where they start, how they got there, and where they’re headed. You only know where you’re going once you understand where you’ve been and the competitive landscape you operate within.

Finally, any model we lean on needs to illustrate what distinguishes underdogs from everyone else.

That being said, together we’re going to build, from scratch, a new comparative model for all humankind. This will help us better understand the fundamental building blocks and archetypal interactions, and provide some needed context for each classification. The first step is to give our new framework a name.

Borrowing from the work performed by the social scientists we referenced earlier, let’s call our updated configuration the Archetype Performance Model, or the APM. We will refer to it as the APM going forward. Next, we need to plot external “Disadvantage.” Let’s place that on the x-axis. Now we just need to place “Passion and Determination” on our new model, which presents us with a small challenge.

Most of us are not particularly adept at recognizing the passion and determination of others. We don’t go around looking for it every day. Also, it can be difficult to evaluate one’s passion or determination, let alone consider them together. Because of this difficulty, we can simplify, reframe, and improve upon the original idea combination. Let’s swap it out for a concept that is infinitely more familiar, practical, and easy to understand; from here on out, let’s refer to it as “Performance.” The idea of performance is a more well-rounded and representative alternate to the constrained ideas of either passion or determination individually or collectively.

In contrast to assessing someone’s passion or determination, our performance is readily visible. It shows up in the words, attitudes, and the personal and professional results we achieve in each area of our lives. Considering our personal performance improves and simplifies our model and the way we talk about our personal and professional success and that of others.

In figure 3.2 we can now plot Performance on the y-axis of our model, which creates the basis for the APM, as shown in the following illustration.

As you can see, Disadvantage runs horizontally, while Performance runs vertically in our new model. We can use low and high as a simple method to further break down the groups along their respective continuums. Now we simply need to add our four archetypes: top dogs, victims, privileged achievers, and underdogs. The placement of each group depends on how their corresponding life experiences relate to their respective disadvantage and personal performance. Here’s how each archetype breaks down by these two dimensions:

Top Dogs: Low performance, low disadvantage

Privileged Achievers: High performance, low disadvantage

Victims: Low performance, high disadvantage

Underdogs: High performance, high disadvantage

As we plot these in the APM, the complete picture begins to take shape, as seen in fi gure 3.3:

And now we have our completed APM. This new visual framework should help you identify in which category you find yourself and consider the archetype of those with whom you come in contact.

In other words, the model efficiently shows us exactly how we’re showing up in the world. It highlights the amount of privilege or advantage we have and matches it to our respective performance. Now we can conduct an objective assessment of both our own place in this model and the places of those with whom we interact. This will serve as a valuable diagnostic and self-assessment tool to consider the privilege and performance of ourselves and others. The goal is not about being judgmental of yourself or others, but about comparing HOW you are performing relative to where you started and the competitive environment around you.

There’s an important correlation that, once it’s seen, can’t be unseen. As we consider the relationship between the four archetypes, here’s a fundamental truth about the respective group interplay.

Top Dogs are to Privileged Achievers, as Victims are to Underdogs.

This statement hinges on our two dimensions of performance and disadvantage. Let’s unpack that a little further. Top dogs have low disadvantages, as do privileged achievers. Victims have high disadvantages, as do underdogs, but notice, too, that each set has a low-performance archetype associated with it. Top dogs are low performing, which makes the high-performing privileged achievers possible. Similarly, victims are the low-performing group in the other combo, which makes underdogs possible.

If you start out as a top dog, the only place for you to go is to stay where you are or move up and become a privileged achiever. (The only exception would be if either became a victim from being exposed to an acute victimization scenario.) Similarly, if you start out as a victim in life, your only options are to remain a victim or move up and operate like a well-rounded underdog.

Furthermore, aspiring underdogs do not need to concern themselves with what top dogs or, for that matter, what victims are doing—both are low-performing groups. Underdogs are, however, in direct competition with the privileged achievers among us. Going forward, they would be wise to concern themselves with two specific goals:

1. Avoid the trap of accidentally performing like victims.

2. Prepare like a credible contender to compete with privileged achievers.

As I intimated previously, the activities of top dogs have no bearing on who you are, how you got there, or where you’re going. However, because they are often so visible to you, it can feel as though you’re in direct competition with them. I assure you, you are not. Now let’s explore each group in a little more detail.

Performance Archetypes

Before we turn the lens of examination inward, there’s utility in fully understanding the perspectives of other archetypes around us. Since the rest of the book is dedicated to the nuance of underdogs and their eff ective performance, we’ll skip them for now to ensure you can readily recognize each group when you encounter them in the real world. Let’s begin by discussing a group you may have heard of before: Top Dogs.

Top Dogs—Low Disadvantage, Low Performance

Top dogs and underdogs both have the word dog in them; that’s where the similarities stop. On the surface, top dogs have all the trappings of success. They have the clothes, confidence, and swagger that normally accompany achievement. They “talk the talk” and have the education, network, and resources to back it up. The only thing is the top dog didn’t earn these advantages on their own; any relative advantage they had was provided to them by the mercy of someone else’s grace.

This isn’t to say, necessarily, that top dogs don’t work and only shuffle through life. There are plenty who do, but many lead typical lives, basking in the advantages they enjoy. Like most things in life, there is a continuum for top dogs. On one extreme are socialites born into wealth and fame. These people truly never have to work at all, if they choose, which is what many of them do.

On the other end are those who are simply born with no real disadvantage or could be considered net neutral. Compared to underdogs, this group would still be considered a top dog, as no disadvantage is still a relative advantage. This might include otherwise middle-class folks who enjoy the advantage of having a stable, loving household, present parents, food on the table, and a family network and educational opportunities to lean on.

In either case, along the top dog continuum this group is content to just get by, not necessarily interested in maximizing their opportunities or pushing themselves beyond their relative comfort zone.

Privileged Achievers—Low Disadvantage, High Performance

The privileged achievers archetype is reserved for those who are advantaged and go on to achieve even higher levels of personal and professional success. This elite class has a powerful one-two combination benefit of being advantaged and has a willingness to work hard and perform. This provides them with limitless opportunities. Perhaps you’ve run into some of these powerful people throughout your life.

This group is characterized by being highly educated and motivated. They are corporate executives, doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, or politicians. At their best they are gracious and philanthropic. At their worst they demonstrate little self-awareness, give little credit to their advantages, or willfully ignore how they achieved their station in life in the first place.

Privileged achievers strive to make a name for themselves, often looking to get out from under the shadow of their privilege. They work hard, to be sure, and leverage their financial resources, connections, and opportunities to run up the score and build lives that most of us can only imagine.

This doesn’t account for every successful person, but I bet you can recognize the entitlement and lack of awareness when you interact with someone with this pedigree. Ironically, this becomes the group with which high performing underdogs will need to compete. Contending with such an established group of competitors makes underdog preparation so vital. However, as underdogs successfully compete and win over time, it should become more and more difficult to distinguish between high-performing underdogs and these privileged achievers.

We’ll continue to explore this idea at various points throughout the book.

Victims—High Disadvantage, Low Performance

The tragedy of the victim is to remain one even after you’re no longer being victimized.

Today, few words create a stronger emotional reaction than suggesting someone is a victim. Yet many of us fi nd ourselves quite literally being victimized at one stage of life or another. That’s unavoidable for the victims of external trauma and disadvantage. It is, however, problematic when one is content to wallow in their suff ering, refuses the support of others, fails to properly prepare, or continues to re-victimize themselves.

To be a victim is to be disadvantaged in a lasting way. While our recovery may be ongoing, the resultant victimhood is meant to be the temporary place in which we fi nd ourselves post trauma. It’s natural and normal to enter this state. It is not, however, meant to be a place where we permanently reside. Unfortunately, this is what happens to many who have been victimized, whether they realize it or not.

The challenge, and the opportunity, is to move forward, one foot in front of the other, to create temporal and spatial distance from our trauma. What other choice do we have? The only alternative would be wallow in victimhood, which is a terrible strategy. As badly as we’ve been damaged, looking for help or support is a good start, with a willingness to accept help when it’s off ered.

And it will be offered. When it’s not readily available, go seek it on your own, and you will fi nd the support you need. I speak from experience on this topic, as I’ve found many wonderful supporters throughout my personal and professional life.

Prior to seeking or accepting support, I struggled with showing up in the world as a victim for a long time, much longer than I needed to. It’s one of the primary reasons I wrote this book—so you don’t have to endure the suff ering, or perhaps for a shorter amount of time than I did. Trial and error will often work, but the learning curve is steep and fraught with painful experiences while you try to fi gure things out on your own.

Performing at any real level close to your potential while acting like a victim is impossible. This is true whether you are conscious of your victimhood, in denial, or blissfully unaware. You can’t get what you want out of life when you’re a victim.

A victim’s lack of performance makes more sense when you consider the defi nition of what a victim is relative to being an underdog:

Victim: Someone who disengages with the world, refusing to heal from personal disadvantage, unwilling to embrace their unique experiences, innate talents and personal development opportunities, relying on an uninspiring story which keeps them from contending for the best opportunities.

In essence, the defi nition of a victim is the opposite of an underdog. Victims suffer from lack of engagement, poor performance, or both. This observation isn’t intended to be a form of victim shaming or judgment. There are good reasons for this response immediately following a traumatic event. Time and separation from negative events are often the best aid for our long-term healing. Eventually, our goal to recover must involve an intentional reengagement with the world around us. As we collect ourselves, the path to future growth, development, and achievement is paved with our successful story, the development of helpful relationships and delivering a noteworthy performance.

We’ll examine each of these topics in more detail in part III.

Sign up for the only newsletter exclusively for underdogs like you.

Once a week we deliver you one new underdog concept, framework, or insight along with a practial way for you to implement it into your life - for free!