The Underdog Curve

Chapter 2 - Disadvantage Creates Three Types of Underdogs

At the age of seventeen, my personal adversity reached fever pitch. This time I was in a bad car accident that changed the trajectory of my life in every conceivable way.

My high school friend and basketball teammate Caleb was driving me home from practice one evening in rural Vermont. We were on a narrow back road that wound along the West River. It was snowing, and the roads were slick. Even though we were going very slowly, our car managed to go off the road. Unfortunately, this was at the point of a sharp corner with a steep bank and no guardrail. We hit the snowbank on the edge of the road; the nose of the car went down as the car went vertical. We went over the bank, end-over-end, for several fl ips, landed upside down, and slid out into the bend of the river.

Fully submerged, Caleb and I were trapped inside the car. I’ll never forget the slow-motion sensation of Caleb brushing my arm under the water as he struggled to get free. I, too, was stuck, unable to release my seatbelt. The effort needed to simply unhook the seatbelt felt insurmountable. Even if I got the seatbelt undone, we were still under water, upside down, and stuck inside the crushed car.

Amid the chaos of being trapped in the car, after a couple of moments, a sense of clarity arrived. Time slowed way down. I vividly remember the instant I recognized the full weight of how dire the situation was. I understood that this was likely how it would end for me. I had been trapped under water long enough that my lungs were aching and my head was pounding. The pain was unbearable. I just wanted it to be over. All of it. I couldn’t suffer for air for even one more second. In that moment I realized I had the power to make the pain stop. A single gulp of water, and it would all be over. I debated giving up and giving into that thought for a split second. The thought of succumbing to my circumstance seemed like a welcome comfort. Anything was better than the agony.

Then, as quickly as that thought entered my mind, the next thought snapped me back into the reality of the situation in another way: I instantly knew I had to find a way to survive. Now there was an intensity of focus that’s difficult to articulate. With every fiber of my being, I focused on the smallest details of the steps needed to get out of my situation. That started with unclipping my seatbelt. I grabbed the seatbelt clasp with my left hand, trying to feel what kind of mechanism it was and how it worked. It was one of the new kinds (the standard kind today) that you had to push down into the buckle. I found the button. Click. Just like that, it released me.

Then, I started feeling around, pushing off the seat then the roof that was crushed in around me. As I turned, struggling to f ind room to move, I wriggled behind my seat to the only open space I could feel. All the while my hands felt around for the next space to move into. Suddenly I felt open water all around me. I could feel myself moving freely. Somehow I had gotten free and could feel myself moving up in the water. A second later my head popped out from the surface of the water. I gasped for breath as though it were the first breath of my life.

I was now afloat in the frigid river. In the moonlight I could make out the bank. I flailed toward it, my body aching, climbing onto the slippery shale along the shore. Disoriented, confused, and hypothermic, I stood up, shaking uncontrollably, and started yelling for Caleb. I didn’t get a response.

Hypothermic, I knew I couldn’t get back in the water. I wasn’t a good swimmer, and my body was shutting down. Instead, with only a cut on my knee, I climbed the bank and trudged to the main road for help.

In a case of pure serendipity, two paramedics on vacation stopped to see why I was standing in the middle of the road flailing my arms. I explained what happened and they immediately went down to assess the situation. Caleb was still in the car and had been drowned for fifteen minutes or so. Long story short, they had to cut him free from his seatbelt, pry him out of the car, and swim him to shore before they were able to eventually resuscitate him. An ambulance arrived later to bring him to the nearest hospital, but the bravery and tenacity of those two paramedics are the reasons Caleb is alive today.

You can see the full-length reenactment video and accident interviews at www.underdogcurve.com/book.

Disadvantages, like this accident, can come out of nowhere in our lives. Or, at times, they creep in slowly and stealthily. Other times, we even open the door and invite them in.

An Overview of Disadvantage

To be considered an underdog, you must have some form of disadvantage, but learning to deal with disadvantage can get complex quickly, and, contrary to popular belief, not all disadvantages are the same. They don’t come into our lives equally, nor do they impact us in the same sorts of ways.

That is why the entirety of this chapter is dedicated to the idea of effectively understanding the different types of disadvantages. As you progress through this book, it’s critical to recognize several fundamental aspects about the topic:

1. First, a quick housekeeping note. To this point in the book, we’ve largely been using the word “disadvantage” to refer to this idea. Because this is such a fundamental underdog component, you may see other references to the idea, like “dark horse,” “underprivileged,” “credible contender,” etc. Usually, these are all used to reference the same idea—someone who is disadvantaged.

2. Second, the word disadvantage is generally defined as either a noun—“a condition that reduces the chance of success or effectiveness”—or as a verb, when one is “placed in an unfavorable position in relation to someone or something.”18Disadvantage Creates Three Types of Underdogs 19

3. Third, the research will show a little later that being at a disadvantage is one of the core aspects of considering oneself an underdog.

4. Fourth, disadvantages come in two main varieties—voluntary and involuntary.

We can invite this pesky idea of disadvantage into our lives, or it can be thrust upon us with little to no warning or recourse on our part. Interestingly, how disadvantage shows up for you determines what kind of underdog you are.

Three Types of Underdogs

Based on research themes and my own experience, there are three distinct types of underdogs.

We don’t have to start from scratch when we think about distinguishing between them either. There’s a closely related framework we can lean on. By way of example, in trauma psychology, practitioners distinguish among three unique types of traumas: acute, chronic, and complex. Considering that many disadvantages result from real trauma, borrowing from the ideas of trauma psychology has the dual benefit of supplying therapeutical insights and laying the foundation for our new underdog classifications.

In psychology, acute trauma develops from a single, high-impact event. An example might be a car accident, an IED explosion, or a natural disaster. The only requirements are that they are high-intensity, one-time, life-changing events that result in sustained or ongoing trauma to their victims.

The next classification of trauma is what is known as chronic trauma. Chronic trauma stems from a repetition of the same or similar types of events. These events are ongoing, over multiple instances, and for an extended period. The sustained nature and diversity of these events help define them as chronic. Consider a child who is consistently physically abused. The abuse happens on an ongoing or renewed basis and would, therefore, be chronic in nature.

Finally, the third way psychologists characterize trauma is known as a complex trauma. This type of trauma is very similar to chronic trauma, with one additional element: betrayal by someone you know and trust. Imagine the physical abuse we mentioned above, but coming from a parent. You would thereby be simultaneously traumatized by the physical abuse and by the psychological betrayal of the abuser.

OK, so now we have a base understanding of these psychology terms and how they’re used. Let’s get to the heart of how we can leverage these ideas to better understand what makes different types of underdogs.

They can be separated in a similar way to how our trauma psychologists lay out their construct, with a few modifications. It turns out that underdog disadvantages can be classified as either acute, complex, or contextual in nature. To arrive at these categories, we keep the general idea behind acute (single event), combine the ideas of chronic/complex into the complex category (ongoing, multiple, and/or betrayal events), and supplement the framework with a new term coined as contextual. That gives us a solid starting point from which to distinguish between our three new underdog types.

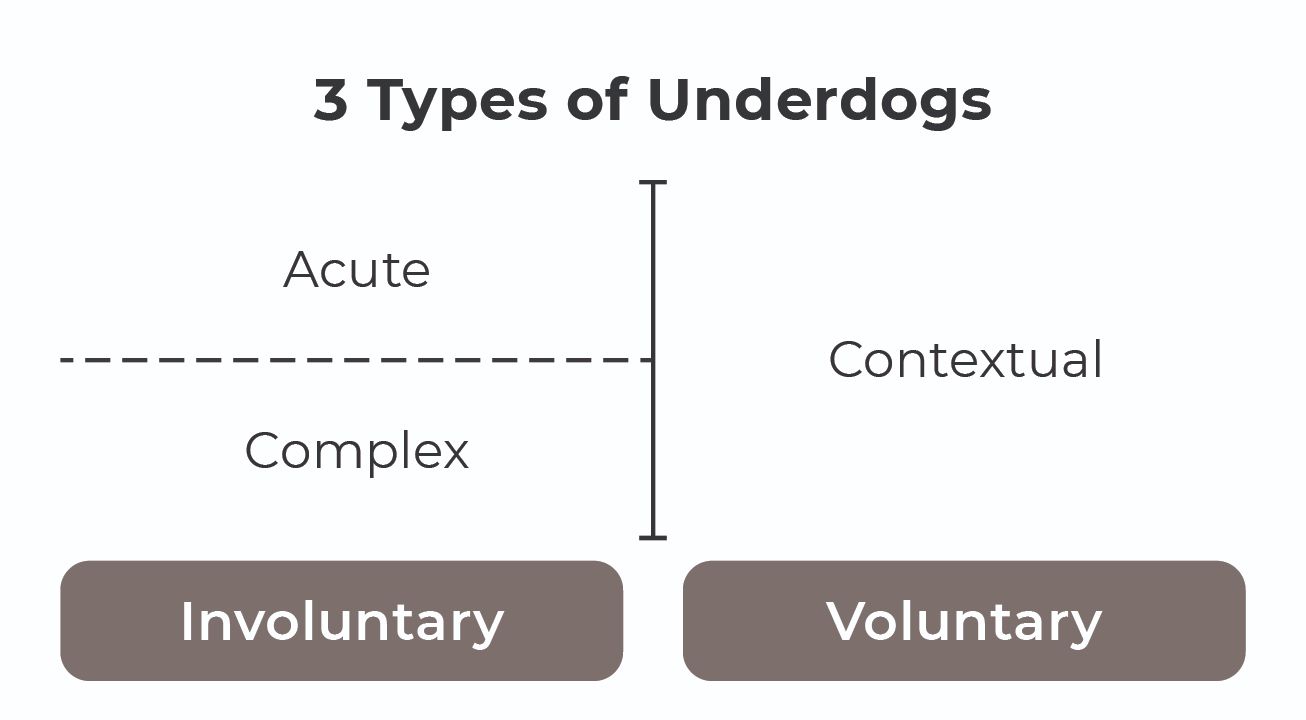

If you recall from the last section, we pointed out that at its core, disadvantage is binary—it’s either voluntary or involuntary. Underdog experiences come to us of our own volition (voluntary), or they are thrust upon us (involuntary) as seen in f igure 2.1.

On one side, you have both acute and complex underdogs who fall into the involuntary category. On the opposing side, you have contextual underdogs who fall into the voluntary category.

We’re going to examine each type of underdog in more detail. Although, before we do, it’s worth understanding the value in distinguishing between them in the first place. There are a few important reasons to break them into three distinct classifications.

This model serves to clear up broad-based confusion or conflation, providing the disadvantaged with a more precise underdog identifier. It also helps to provide context for your own personal traumas, especially as you consider whether you fit into one or more of these disadvantaged classifications. It offers the added benefi t of highlighting the idea that the acute and complex types are at one time victimized, while contextual types are not. Finally, the model serves to promote a willingness for underdogs to openly identify with their respective identifi er now that they have a clearer understanding of the diff erences between each type. Now, let’s consider each classifi cation in more detail to get a better understanding of exactly what makes each type unique.

Acute underdog: Someone who involuntarily experiences a singular, nonrecurring life event that leaves them disadvantaged in one or more ways.

An example might be a soldier who loses her leg in a war. Leading up to that point, she may have never otherwise been disadvantaged or considered herself an underdog. This new, involuntary, life-changing event has sprung upon her in a single occurrence. This one experience was so abrupt, impactful, and life altering that she now has one or more persistent disadvantages to overcome. The new physical and psychological disadvantages place her squarely in the realm of being an acute underdog, who is victimized by her trauma until she has healed. (Another example would be the story of my accident from the opening of this chapter.)

Complex underdog: Someone who involuntarily experiences an ongoing series of similar events or a variety of disparate life events that leaves them disadvantaged in one or more ways. This may or may not include the betrayal of trusted friends, family, or confidants. Generally, this class of individual experiences numerous impactful events over an extended period.

A good example of a complex type might be a young man who is sexually abused by a priest throughout his adolescence. The abuse likely happened on multiple occasions, in a similar manner, over a period of months or years. The compounding factor in this scenario is that the abuser also happened to be someone the boy should have been able to trust, thus exacerbating the trauma by adding personal betrayal to the abuse. This would make him a complex underdog due to the chronic nature of the sexual and psychological traumas and the resulting disadvantage. Complex underdogs are victimized across disparate types, modes, and/or durations of trauma.

Finally, we come to the other side of the coin: contextual underdogs.

Contextual underdog: Someone who voluntarily chooses to participate, engage, or compete in an environment that places them in a contextually disadvantaged position relative to other participants, as seen from an objective viewer.

A simple example of a contextual type might be if you decide to enter the world of race car driving. I’m willing to bet that you’re not a professional racing driver today. By voluntarily entering that arena, you are circumstantially disadvantaged when compared to other professional race car drivers. You don’t have the skills, training, or possibly even the innate talents to ever be a race car driver. You would be competing against professionally trained drivers, and, therefore, you would be at a disadvantage, albeit one of context only. You can decide to do something else at any time and thus change the context of your participation in your disadvantage. In other words, contextual underdogs can never be true victims. (Unless they experience disadvantage in other ways too.)

In acute or complex scenarios, notice how the individuals are victimized by one or more events in their lives due to outside forces. Someone or something outside of their control has projected the disadvantage into their life. They are unaware of and generally unable to avoid this kind of initial victimization. By contrast, in the contextual scenario, one knowingly enters their chosen arena and voluntarily subjects themselves to disadvantage; therefore, they cannot be victims but knowingly disadvantaged (and willing) participants.

The idea of being an underdog has been misunderstood for a long time, mostly because we’ve been talking about them as though only one kind exists. Now underdogs finally have the nuanced clarification they deserve.

Sign up for the only newsletter exclusively for underdogs like you.

Once a week we deliver you one new underdog concept, framework, or insight along with a practial way for you to implement it into your life - for free!