The Underdog Curve

Chapter 10 - Authentic Stories

A few years back, as I started doing research for this book, I was driving around town with a corporate colleague, Emory. Emory and I were debating the merits of sharing your personal story with others. He is an underdog by any measure but wasn’t comfortable sharing his story with friends and certainly not work colleagues. Candidly, he came off as a little guarded sometimes, and I noticed it was holding him back in certain work situations.

I was encouraging him to be willing to be more vulnerable, trust folks, and share a suitable version of his story. He didn’t seem particularly persuaded by my arguments, at least not initially.

Then something serendipitous happened.

We arrived at the restaurant to meet some of our business partners for lunch. This was just after COVID restrictions were easing up, and everyone was excited to be mingling in person again. We went around the table, taking turns introducing ourselves. The leader for our partner’s fi rm went last for her group. She made a point of highlighting how the charitable, giving aspect of our fi rm was well aligned with the values of her fi rm and their local team.

She shared that she, too, was on the board of directors for a worthy charity working to solve homelessness in her area.

It was at this point that she made a vulnerable admission. She told us that while she was passionate about solving the homelessness crisis locally, she felt somewhat disconnected from homelessness itself, having no firsthand experience with it. Her comments, while perhaps a little out of touch for a board member of a charity supporting homelessness, were well received by the group.

As it turns out, I had a fair amount of personal experience with homelessness as a child and even a little as an adult. When she finished sharing her thoughts, I spoke up, thanking her for sharing her experiences and her commitment to the cause. I related how homelessness is an important cause, as many people find themselves homeless at some point in their lives. I shared with the group that I had some firsthand experience in this area. In truth, I had been homeless for much of my childhood and even briefly as an adult as recently as 2009.

The table became very quiet for a few seconds. Then one of the other group’s leaders commented that he didn’t know that about me and thanked me for sharing. Several others echoed him with their thanks for my willingness to share so personally with the group.

Immediately after those comments, a woman jumped in to share that she had been working with her sister who had been going through some homelessness recently. She related how difficult it was emotionally to see her deal with this and talked about some steps she took to try to support her sister through that time. By now, the whole table was engaged, and we spent the next half-hour on the topic—questions fl ying, experiences, opinions, and perspectives. Everyone had an experience or insight to share.

Without me saying a word, as Emory and I jumped in the car to leave, he said, “You made your point. I can’t believe you shared such a personal story with that bunch and how well they responded to it. I also can’t believe how much experience other people have with homelessness.”

As counterintuitive as it sometimes can sound and feel, our personal story is often the one others need to hear the most.

Underdog Story Blueprint

This chapter is laid out to cover the seven-step process for what is called the Underdog Story Blueprint or USB. Each part of the blueprint has its own section laid out in practical detail. Before we review each part, it’s helpful to re-review the Underdog Equation we outlined earlier in the book to see which part we’re tackling.

Underdog Equation

(Two Authentic Stories—Victimhood) + Intentional Relationships + Differentiated Performance = Underdog

This chapter is all about the fi rst part of the equation—our two stories and the removal of victimization themes. From there, we will address each part of the USB process outlined below:

1. Words matter

2. Two stories, not one

3. Removing victimhood

4. Three goals of sharing

5. Microtargeted sharing

6. The power of figurative language

7. Your story takes flight

The starting point of the USB framework is understanding that before we can ever craft a story worth sharing, we must first have a story worth telling ourselves.

Words Matter

“Watch your thoughts, they become your words; watch your words, they become your actions; watch your actions, they become your habits; watch your habits, they become your character; watch your character, it becomes your destiny.” —Lao Tzu

My former boss studied law at Harvard. For my own amusement and to thoroughly embarrass him, I used to slip in that little nugget when introducing him to our partners. Over the years, I found many Harvard jokes to help me poke fun at him, but my favorite goes something like this:

How can you tell if someone graduated from Harvard Law?

Don’t do anything—they will usually tell you within two minutes of meeting you.

Kidding aside, I consider myself fortunate to have worked so closely with many dynamic attorneys over the last ten years. I learned many useful skills through engaging and collaborating with them. If there’s one lesson that stands out above anything else, it’s that our words matter!

This is especially true for those who have experienced historical trauma.

The words we choose set the stage for how our interpersonal interactions will go in every situation. Lawyers choose their words carefully so as to not be misunderstood. They are intentional with both their choice and quantity of words. This helps them precisely articulate the message they wish to convey while not giving away their motives or oversharing irrelevant or potentially damaging details.

Underdogs would be well advised to borrow a page or two from the lawyer playbook. Interestingly, the disadvantaged share some compelling things in common with lawyers. Both deal with high stakes in their daily lives, and success for both hinges on their choice of words. Lawyers present their case in the courtroom or the boardroom, while underdogs submit their story in the court of public opinion. One could readily argue that public opinion is a far tougher and less fair judge and jury. The difference is that when it comes to underdogs, their words matter far more because the stakes are much higher. A lawyer might lose a case, negotiation, or an argument, but they go on to live and debate another day. When underdogs get their words wrong, they risk losing something far more precious: the relationship and potential advocacy of others. The loss of advocacy or the inability to attain it has a tremendous impact on the trajectory of our lives. Thus, the words we use in our interactions with others matter a great deal.

Here are a few of the questions you need to answer before crafting your story:

• Which words, experiences, and ideas from my story should I include or possibly avoid?

• When is it most appropriate to share these thoughts with others?

• With whom should I share my story?

Answering these questions and learning how to share your story can help you avoid significant heartache and some tough lessons. I spent many years and experienced substantial embarrassment sharing the wrong kind of story with others. I learned the hard way that developing the right stories is one of the most powerful tools to have in your toolbelt. Your story can help you get anything or go anywhere you want in life. Or those same stories can hold you back, keeping you from progressing or growing in your personal and professional life. In the end, your overall success largely depends on the quality of your story, which is formed by the words you choose to use.

They can inadvertently make us sound like victims and nothing more. Sounding like a victim turns people off. Our initial stories often make us sound disingenuous or insincere. Victims tend to overshare and use unrelatable language that alienates others. They overtly tell people they’ve been victimized. Or they set the stakes too high by either exaggerating their story or using hyperbolic language. The use of any one of these is enough to repel others. We often use several of these tactics in our story, then wonder why people seem to tune out.

It’s not that people are averse to underdogs. We’ve seen how much people relate to and are drawn to support them. Their aversion has more to do with the words we use and the way we share our story. People are willing to support credible contenders but either respond with unproductive sympathy or immediately give up when we sound like victims.

Underdogs will never develop advocacy if their words convey them as victims.

There’s a counterintuitive approach at work when we successfully share our story. You don’t have to tell someone how you identify yourself. Quite the opposite is true. One study found that your underdog message is “more potent” when you allow this label to be applied to you by others.58 People are smart. They recognize an underdog when they see one. They can put together who you are through your word choice, without you telling them directly. Instead, be clear but don’t overshare, honest with a hint of intrigue. In other words, let them discover who you are. Telling them is not making the case you hope it does.

Underdogs should take great care of their reputation. The researchers from the study above suggest that eff ectively navigating your personal and professional interactions is a critical “impression management tactic.” Be proud of who you are, but don’t wear your heart on your sleeve. Share your story, but do it in a way that’s authentic to you and respectful to others. You’ve likely seen how privileged achievers leverage a well-formulated narrative for their benefit. While their story sounds very different from yours, it always positions them in the best light. You need a story that can carry the same weight and gravitas for you.

Ultimately, our words matter; choose them carefully.

Two Stories, Not One

There are two essential stories that we all use to make it through the day. The first is the story we tell ourselves. The second is the story we tell others. Both narratives are developed over time and intended to convey similar things—who we are, where we came from, and where we’re going.

On the surface, it can seem like the same story could be used for both audiences. That’s not true. It is a similar story, but not quite identical. One is used only for you as a private story. The other is intended to be shared with others—your public story. For them to be appropriately tailored to those two distinct audiences, they need to be crafted with two different objectives in mind. More on this in a moment.

For now, it’s enough to understand that the personal narrative in your head is far too raw and detailed for the personal consumption of others. Communicating with people in the same way we use self-talk is a recipe for disaster when our long-term goals involve developing meaningful relationships.

These two stories have the same facts and elements. The public story is more refined, and the conveyor must consider how it will be received by someone who doesn’t have the same experiences in life, especially when shared with the more advantaged among us.

In his book The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell highlights that linguists sometimes use the idea of “temporal narratives” to describe our attempt to integrate the events and actions of our lives into a cohesive story structure.59 While I don’t agree with him much when it comes to his opinions on disadvantage being desirable, I can defi nitely buy-in to the utility of temporal stories. In essence, our public story acts as the glue that holds the moments of our lives together. It supplies context and meaning while serving to smooth out the volatility we’ve experienced. It’s how we sensibly convey our unique experiences while making it more palatable for a casual audience.

Stories allow us to contextualize the disparate events, suffering, accomplishments, wins, defeats, and the ups and downs of our lives. If it weren’t for our ability to make sense of and get meaning from the random and difficult events of our lives, underdogs would be living in a constant state of volatility whiplash. Instead, we develop stories, and that helps us maintain our sanity and effectively engage with others.

Story transforms our collection of disparate experiences into a portrait of our lives.

Stories are at the very core of who we are. The collection of our private and public stories acts to establish a cohesive, central persona for us. Over time and as we share our stories, they become a signifi cant part of our identity and even our personality. We quite literally become our stories over time.

Since they’re so integral to our lives, it seems like we should be careful with how we develop them. Unfortunately, underdogs often let their stories run amuck and get the best of them. That leads to oversharing or telling stories that do not move relationships forward. Instead, we should be guarding and carefully curating, honing, and managing them.

Left unattended, our stories do not accomplish what we intend. One day we look around and wonder why things aren’t going well for us. Well, that inaccurate, disempowering, uninspiring, or alienating story is at least partially to blame.

Paraphrasing James Carville from Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, “It’s the [story], stupid.”60

Don’t worry—we’ve all been there. Allowing the story to write itself is not a good strategy; it’s a very bad strategy. Therefore, starting today, let’s commit to do something about it.

Constructing your story is like putting together a puzzle.

You start with a box full of pieces. You have an idea of what it should look like from the cover of the box. You open the box and pour out the pieces. You start to organize by side pieces, corners, similar colors, etc. That leaves you with a few different piles.

Start by finding the corners. Then you put the edges together to create a frame. Slowly you start to find two other pieces that go together, then a third, and so on. Ultimately, you put the whole puzzle together. It takes a little time, patience, and diligence, but the finished product is worth it. Then you can save the puzzle by varnishing it and sticking it on your wall to share with others.

Unlike a puzzle, the personal picture you follow is one of your own choosing. Only you get to decide what the finished product looks like. Hopefully it’s an image that simultaneously refl ects your truth and is palatable to others.

You can and should exclude most of the rough parts. Be sure to include the parts that are inspiring or empowering. The beautiful thing about crafting your story is that you decide what goes in your image and what doesn’t. No one should ever know the nitty-gritty details unless you want them to. As always, you’re in control of what’s included and what’s omitted.

I believe that underdogs have a moral imperative to share their story with the world. I also believe it should be well crafted and refi ned to support you. When you begin to curate the raw materials of your story, it’s important to keep in mind how you want your audience (you or others) to react to the story when they hear it.

The order of story development matters too. It’s impossible to craft a compelling story for others while there’s still a disempowering or poorly crafted version running through your mind. That said, let’s have a look at the fi rst story we need to update for personal use.

Private story: The internal narrative we craft and repeatedly tell ourselves about who we are and how we got that way. It should be accurate, compassionate, appreciative, and empowering. This version is the one responsible for propelling you forward and serves as a wellspring of motivation to overcome personal adversity. This is meant only for you.

To begin with, it’s essential that your story is factually accurate and objective. As it relates to your disadvantage, your private story should not portray your former or current circumstances as being better or worse than they really have been for you. Don’t exaggerate how bad you may have had it or how much things still effect you today. By the same token, don’t discount or sugarcoat the events of your life. It should be an uplifting tale of both your experiences and the steps you’ve taken to surmount them.

Drafting the right kind of story for yourself will require some vulnerability, candor, and honesty. It might dig up some feelings for you. My story certainly does, but that’s OK. Ask for help from friends, family, or a therapist if you need some additional support. It’s worth going there to optimize the story that runs through your mind every day. When done correctly, it might even shift the perspective you have on what you’ve been through.

Our private story should show some self-compassion and allow room for forgiveness of yourself and others. Finally, it should motivate and empower you to seek personal improvement and become a better version of yourself. Your story is a part of you but does not define who you are, only what you’ve been through and how you made it out.

Crafting this story is an important first step toward your mental health and well-being. In essence, we have a personal responsibility to take care of ourselves. Having a well-crafted private story is a critical form of self-care.

Once you have your private story organized and crafted, then and only then should you work on your public story. This is the version of your story you’ll share with acquaintances, friends, lovers, colleagues, and anyone else you decide.

Public story: The refi ned external narrative we create for others, which should be accurate, inspiring, and travel well across diff erent conversational contexts. It is a story that provides others with a glimpse of your experiences and should help you develop support along the continuum of empathy, attunement, and advocacy. This story is intended for family, colleagues, prospective friends, or anyone with whom you decide to share it.

Our public story originates from the same place as our private story. One key diff erence is the rough edges are sanded smooth. It is our story turned relatable for the masses. The intentionality and refi nements help us avoid conjuring it on the fl y, allowing you to share it with victims, top dogs, or privileged achievers alike. They will each hear what they want to hear when you tell it.

The story needs to be inspirational, subtly illustrating how far you’ve come with a hint of what you’ve been through. The goal should be to let your audience refl ect on exactly what you’ve endured and what your experiences might have felt like for you. Their first feeling should be surprise when they consider where you are today, despite what you’ve endured.

It’s not our job to tell others how they should feel. Children try to make others feel the way they feel about an experience early on in their maturity and development. Adults need to allow each other to come to their own conclusions and experience their own feelings. It’s not our place to tell someone how to feel about what we share with them.

In my experience, people are going to feel how you make them feel. If your story is well crafted, your message will land the right way with those open to receiving it. Remember, it won’t resonate with everyone. That’s understandable and OK. Not everyone is going to end up being an advocate for you or even remain in your life over the medium to long term.

You’ll know your public story is landing when you see others relating to your journey. Often, they will share their own struggle with you almost immediately after you share your story first. It’s one of the numerous benefits of being vulnerable and willing to share. Ultimately, your story should move people to want to support your goals.

In 2015, I was asked to speak at a local university a couple of times to share my personal story with graduate students, in the context of “food insecurity.” It was interesting how well they responded. While at first reticent, several students approached me one-on-one after the talks. They expressed how much similarity there was between our stories and how appreciative they were for someone sharing that kind of story with a broad audience. To hear that was rewarding and telling. It was a solid reminder that there are more people than we realize going through the same or similar difficulties as us. That means there are opportunities for us to relate, connect, and develop relationships with many more like-minded and similarly experienced people than we expect.

Having a well-crafted public story is critical to eliciting the faith, trust, and confidence of others. You will start having more positive experiences as soon as you get your stories tuned up—in your own mind and with those whom you engage.

Removing Victimhood

“Freedom is what you do with what has been done to you.” —Jean Paul Sartre

We’ve all heard the cliché “Practice makes perfect.”

While that’s a nice thought, it does little to capture reality. First, it couldn’t be just any old kind of practice to make something perfect. Like my high school basketball coach used to tell us, perfect practice makes perfect. While his point was well intentioned and received by teenagers, it’s less useful for us as high-performing adults. Second, there’s a flaw in the underlying premise that perfection is something that’s ever attainable. It’s merely a pursuit, not a destination, as perfection is rarely obtainable and never sustainable. There’s one thing for sure, however: we can never develop our most inspiring public story for others if we continue to include elements of victimhood in it.

In the Underdog Equation, we show the removal of victimhood simply because there’s no place for it. It isn’t meant for you. Let’s leave the victimhood to the victims.

As you craft and later share your stories, the removal of victimhood from your narrative is an absolute necessity. Removing this type of language or tone requires increased personal awareness. People are only inspired to support those they view as credible contenders. Credible contenders need to be viewed as overcoming their disadvantage, not wallowing in trauma. When we convey even a hint of being a victim, people shut down before we can f inish our thought.

As we begin the journey to leave victimization behind, our words and stories should keep up with our progress. It’s never cute or in vogue to be a victim when you’re not actively being victimized. In other words, don’t dwell in a state of ongoing victimhood.

What does poor practice have to do with crafting an effective underdog story?

Well, quite a lot. You may not feel like a victim now. You might also think the cynical or contrarian attitude you display is the key to your success. In reality, it’s a defense mechanism used to shield you from being honest with yourself and others. It’s having the effect of holding you back, not propelling you forward, and it’s at the core of why you don’t have what you want out of life, even as you read this passage.

Our negative, victim-oriented thoughts creep in insidiously. The process is slow and incremental. Our friends and family contribute to them. Gradually we begin to reinforce them too. Eventually, the story wears grooves into our thoughts until we’re left with a disempowering story arc. That bad story runs on repeat in our minds. Worse still, we go on to share it with others. The constant negative reinforcement of this story arc makes us believe it too.

Years go by and you look around, wondering why life hasn’t been kind to you. The reality is, in a sick twist of fate, underdogs inadvertently end up doing this to themselves. We don’t mean to; it simply happens over time when our thoughts are left untended. Congratulations! We are victims again, this time by our own hand.

Underdogs deserve better.

The trouble is that being a victim or using the language of victims is a defensive strategy. You know the well-known sports idea that “defense wins games”? Yeah, suggesting that defense alone wins games is somewhere between disingenuous and bullshit. At some point you need to put some points on the board or you’re going to have a long bus ride home with nothing to show for it.

Underdogs don’t practice playing defense; they play off ense to compete for what they want as credible contenders.

As we’ve alluded to throughout the chapter, our words can have a lasting eff ect. They matter. They also tend to create mental ruts in our mind. When you say something long enough, it tends to take on a life of its own. It can even make an embellished or alternative version feel right. That holds true for our stories too. Again, it does us no good to craft two new stories, weaving in even a subtle subtext of victimhood.

This is going to take some time to perfect. We need to practice removing all these subtle notes, tones, words, phrases, and attitudes from our stories. Strive for perfection but show grace too. Recognize that this is going to be a journey. We can cut ourselves some slack while still holding ourselves accountable for using better words and ideas.

Start by recognizing when and where these victimized words, phrases, or expressions show up. Then reframe them to appropriately align with how you would like to come across in the world around you and, frankly, who you were meant to be.

Remember what’s at stake here: valuable relationships and eventually advocacy. It’s time we get our words together and stop sounding like a victim once and for all.

Three Goals of Sharing

At this stage, you’ve got a good sense of the broad goal of establishing advocacy. That’s a good start, but advocacy is not some theoretical exercise. It’s a tangible byproduct of developing the right relationships. And every relationship starts with an initial conversation.

Each conversation you have as you move through the world is unique. Often the people you’re interacting with are complete strangers. They know little to nothing about who you are, your experiences, where you come from, or what you’ve been through or achieved. Whether it’s a new love interest, an acquaintance, or a hiring manager at work, it’s helpful to have a cohesive narrative ready that can potentially move the relationship forward. Strive to have your story resonate with everyone you encounter, but expect that not everyone will get it. That’s OK.

When you first meet someone, it’s impossible to know whether it will turn into a relationship at all. You need to figure out if they’re someone you like. That feeling should be reciprocated, but even then, it doesn’t guarantee a relationship. Rapport can be diff icult to establish because many people are guarded. The context of the meeting matters tremendously as well. Sometimes it’s hard to believe that we ever get to know anyone. In the end, the only thing you can hope to do is put yourself out there, share a little slice of who you are, and gauge and respond to the reactions of your audience to see how things play out.

During the early stages of dialogue with someone, as you’re getting to know them, and when the time is right, the initial story you share has three primary goals:

1. Pique curiosity

2. Hint at adversity

3. Leave ’em wanting more

That’s it. Don’t try to boil the ocean in your dialogue with someone. Your intention is to get these three simple goals across. Here’s an example I’ve been using in some form or fashion for about ten years when I’m meeting someone new and the opportunity to share about myself comes up:

“I had a rather tumultuous childhood. We lived in cars for much of my childhood, and I went to eleven schools growing up.”

You’ll notice that I’m sharing some details but doing so in a way that is matter of fact, not victimized. I characterize my childhood to pique curiosity as to what I mean by “tumultuous.” Then I share that I lived in cars and went to eleven schools. Most would consider that some form of adversity. This is short and quickly delivered. I don’t linger on the delivery or expect a response. That leaves people wanting more. It’s like dropping a porcupine in someone’s lap to gauge their reaction.

And the results are about fifty-fifty. Half the time I get an odd look, and we move on. No harm, no foul, with little risk, exposure, or loss on my side. I haven’t given up anything personally material or been overly vulnerable. At least the other side got a glimpse of where I come from. Even when the other side doesn’t engage, if we continue to maintain contact, they have a decent sense of what I’m about.

The other half of the time is when things start to get interesting. Every other time I share this quick synopsis of my life, the other person will ask me a follow-up question. They ask me if my parents were in the military (they were not). Or they ask about what it was like living in cars. Or what I mean by “tumultuous.” Or how I managed to even get through school, having gone to so many. These and a hundred other variations of these questions originate from a two-sentence story.

The question they ask is less relevant than the opportunity it provides to engage in a more robust dialogue as we get to know one another. I will usually follow it up with some added details and see where things go. Depending on how much I share, people often reciprocate with a nugget about their own lives. It’s often on the less traumatic side, but that’s fine. Our human instinct is to try to relate with one another. Remember, it’s not a competition. My goal is to get to know them and for them to get to know me.

You can learn a lot about the people you encounter by listening. You will pick up on the story they tell others, which has a lot in common with—you guessed it—the story they’re telling themselves too.

Microtargeted Sharing

An interesting, compelling, and differentiated story is worthless if you share it with the wrong people. Fortunately, as the purveyor of your story, you make the decision about when and where to share it—or not.

\Wearing your heart on your sleeve, telling everyone you come across about your personal adversity is not a good strategy. Again, this a very bad strategy. You don’t want to be known for being that person with the sob story. Don’t treat your interactions with others as therapy, unless, of course, it is therapy. In that case, share away to get your thoughts clear.

It’s not about your intention when you share your story; it’s about how it’s received. Remember that communication is a twopart process—sending and receiving. What you send isn’t always received as well as you hope or think it should be. In general, people want to be engaged. And who do they prefer talking and thinking about more than anyone?

Themselves. I hate to be the one to break it to you, but…

Your story is not about you, at least not initially. It’s about someone else seeing themselves as the hero of their own story through the one you share with them. Your story is a conduit to help others feel good about themselves, by wanting either to support you or to view their own experiences through you. This is allowable, and it’s better to understand these motivations from the outset.

Before you decide to share your story with anyone, there’s an important three-part microtargeted sharing framework that considers the utility, meaning, and impact of what you’re about to share. Each part of the model offers an important question related to whether you share your story or not.

Microtargeted Sharing

Utility—Will sharing my story help the other person better relate to or understand my point of view?

Meaning—Will sharing my story provide improved context or make space for the other person’s experiences?

Impact—Will sharing my story enhance our mutual connection and move the relationship forward?

Be honest with yourself as you refl ect on these questions.

If the answer to any one of these questions is yes, then you’re probably on sound footing to share your story. The trick is to be conscious of your evaluation and only share intentionally. If you find yourself midstory and don’t know how you got there in the first place, it might be time to tactfully transition back to common ground. If it feels awkward for you, you better believe it’s awkward for your audience too.

Finally, avoid being manipulative in your decision-making process, but be intentional. Tell only who you must, with the intentional goal of supplying utility, meaning, or impact to establish the best kind of relationships.

Figurative Language in Your Story

If you want to cut through the noise and get your story noticed, you need others to both listen to your story and really hear it. That includes the clarity and meaning you originally intended.

When I was in the US Army, I learned a valuable lesson about the importance of communication. In the service, communication is a high-stakes art. We used a host of different tactics to ensure messages were clear, discernable, and readily understood. That requires consistency across messages and time. The easiest way to ensure consistency is to have everyone speaking the same language, which includes similar words and nomenclature for people, places, and things. To consistently describe them we used a specific tool called the phonetic alphabet.

If you’ve ever seen an action movie, you’re probably already familiar with the phonetic alphabet. It’s the Alpha, Bravo, Charlie way to spell out words or refer to something in a systematized and consistent manner. People use this or other versions all the time in air traffic control, truck driving, and even in customer service organizations. Oddly, they all have their own phonetic alphabet, or they make one up as they go. (They should just adopt the wellknown military version, but I digress.)

The military keeps things simple, and so should you. Communication is an easy concept to understand. Fundamentally, it’s a function of two parts—a sender and a receiver. The message you send should be the one you intended, clearly articulated and identified by words that resonate and are easily recognizable and understood by the receiver.

In the military, the stakes are often literally life and death. In our day-to-day world, the stakes are less dire but still important. For underdogs, the ability to ensure our message is received appropriately determines whether we develop the relationships we need and whether we can build advocacy over time. That’s not nothing.

There’s a common mistake I hear underdogs make all the time. They use figurative language that is abrupt, tones that alienate, or words that make others uncomfortable in normal conversation. As a result, they come off as unrelatable, defensive, immature, victimized, unaware, or simply as someone that cannot be taken seriously.

Go ahead, ask me how I recognize these so readily. I used to use them too—that is, until I figured out they were having the opposite effect of what I intended them to do.

This usually happens when we’ve failed to spend time intentionally crafting our stories. Our ideas, narratives, and goals are not clear in our own mind. In other words, we end up sounding like a victim and leave a trail of missed advocacy along the way.

Let’s look to the professionals when it comes to putting words together—writers and authors. Trust me when I tell you that I’m not referring to myself. I’m very much on a learning curve when it comes to this whole writing thing. I mean the quintessential writers who have captivated readers by writing stories that endure for centuries. They know how to put words together. To do this, they use a litany of literary devices to effectively share their stories, attract attention, and capture our imagination.

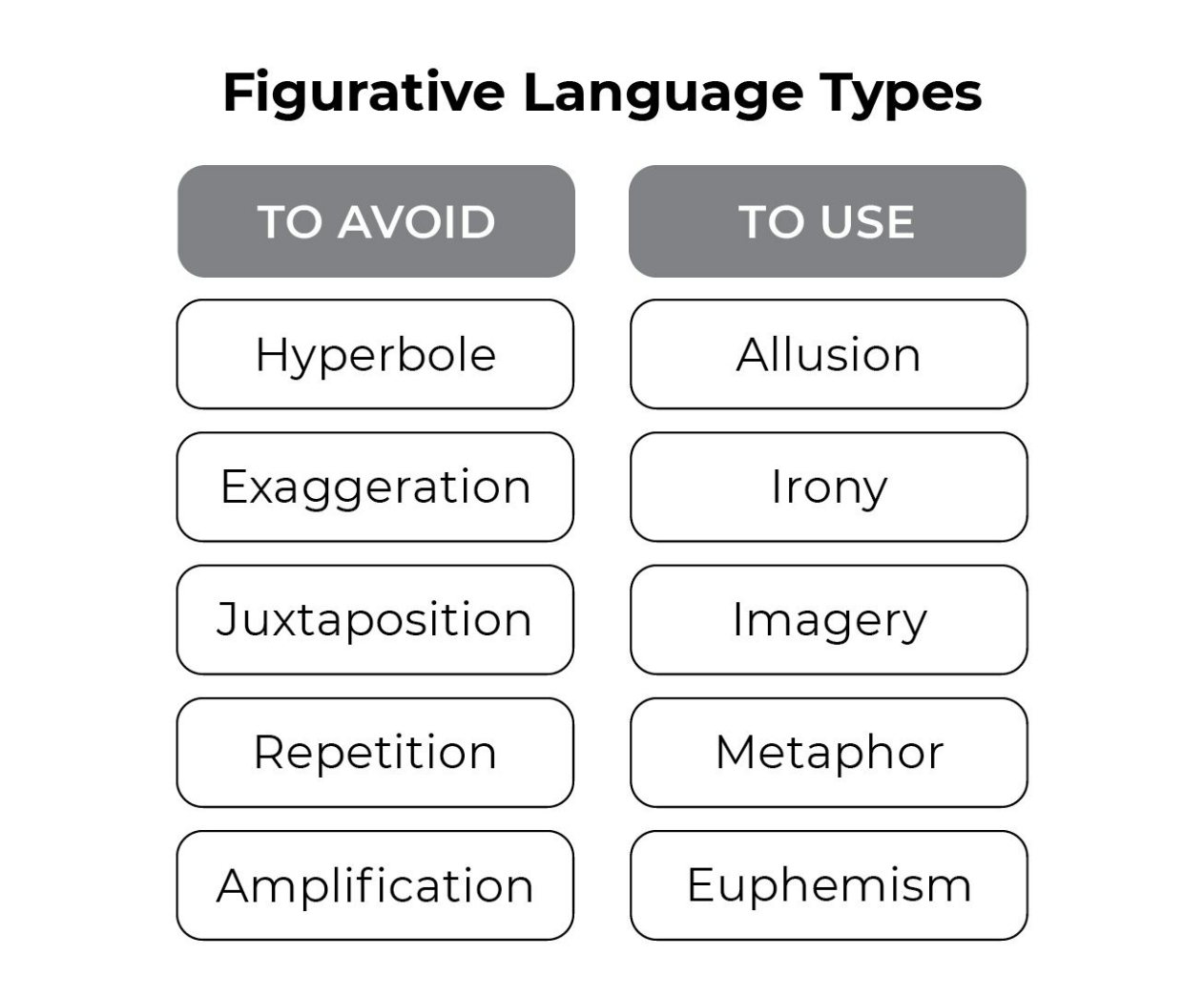

Figure 10.1 provides an overview of the types of figurative language that should be both used and avoided:

To get a complete list of the various types of figurative language and real-world examples of what these look and sound like, visit here.

The tone and imagery of your story matter a great deal. The words in the “to avoid” column are often used as a shortcut to try to make our stories stand out and grab attention. They do get attention, but not the kind we’re after. Instead, all they do is alienate our audience, turn them off, or ensure that they shut down and avoid getting to know us. That is quite literally the opposite of our intended goal.

I’m no psychologist, but I have to believe our ego is tied up in the use of the wrong types of figurative language. While it might make us feel good to use hyperbolic language temporarily, it’s a case of the right goal but the wrong strategy.

Instead of being so direct, make your point by piquing curiosity. Use a euphemism to make your point, and pepper in some imagery or allude to the disadvantage. People are smart. They will get your point and come to their own conclusions about what you’re trying to get across. They also need to decide whether they want to engage with you on this topic or not. Remember, you don’t control how they respond. You win when you share your truth in a way that’s relatable to most people. Not everyone is going to be your new BFF.

Here’s a bad and better example of an underdog narrative of someone who experienced childhood trauma. Let’s look at the bad example first.

Bad Example:

“I was the poorest kid in the country growing up” (hyperbole).

“I barely ever had food to eat like other kids” (juxtaposition).

“Being as poor as we were, we didn’t have a house to live in, so I had to get dropped off to school from the car we slept in the night before” (repetition and amplification).

This might all be or feel true to you. That, however, is not the point. Because this is so specific and unrelatable to so many people, it makes you sound dramatic and victimized instead of empowered and capable. To paraphrase a well-known underdog hip-hop artist, sometimes what you say and what you mean come across as two distinct things.

This is an example of oversharing and preventing others from recreating your story in their own mind’s eye—#TMI (too much information). It supplies so much information that you leave nothing to the imagination. That makes others wonder, “If they’ve got this much baggage at first glance, what do they have hiding just below the surface?” Not a great way to entice someone to get to know you better or open the door of opportunity.

Alternatively, here’s a better example to convey the same experience while allowing the story room to breathe.

Better Example: “I had a rather tumultuous childhood” (euphemism). “We lived in cars, and I went to eleven schools growing up” (imagery and allusion).

Short and sweet. This version tells others where you come from and what shapes your thinking without getting too personal too quickly. It also piques interest, hints at adversity, and leaves ’em wanting more, as we talked about in the last section. Leave out the gory details until you know someone quite a lot better—or until they ask. At that point, you have more flexibility to expand your story and enter a deeper dialogue with them.

Experience suggests that the right story will evoke questions from the right audience. When they want more, they’ll ask for it. Until then, focus on making your story as interesting as possible.

Remember, your story won’t resonate with everyone. That’s a good thing. It will also be effortlessly polarizing. When your story is structured using the right figurative language and the three goals, you can relax knowing you’ll attract the kind of people who are genuinely interested in getting to know you better.

Your Story Takes Flight

Not all conversations are created equally. Act accordingly.

Up until this point, we’ve talked as though all conversation types and depths are the same. We know that is not the case. Therefore, we need to consider how to tailor our message to the appropriate audience. That level of sharing depends on trust and where your relationship is with the other person. More on the topic of trust in the next chapter.

Talking about disadvantage is risky for you and others. Therefore, the responsibility to consciously recognize the right level of engagement lies with underdogs.

I refer to these levels of engagement as the flyover, jump altitude, or tandem landing level of storytelling. The audience matters for each, as does the depth at which you relate your story. Not all stories resonate the same, and not all conversations require the same level of detail. While the underlying story is the same, it’s the depth of detail that matters. As a result, as you get better at crafting your story, you can tailor them to fit distinct audiences.

In this section we’re addressing how deep you should go with someone. This is the enhanced version of story development. One builds on the other. Like most things in life, you need to get good at the fundamentals before you try more advanced techniques.

Let’s take a deeper look at the characteristics of your three-story levels—the fl yover, jump altitude, and tandem landing stories.

The Flyover

Explanation: Flying at thirty thousand feet. You’re high enough to see the broad landscape of your story but with little detail, perhaps only a couple of the larger landmarks. You’re moving quickly, covering a lot of ground but at a high level. The passengers can anticipate the destination and agree to go to the same place you’re headed. A smooth and shallow conversation that merely insinuates your hardships is more than enough to make your point at a high level.

The flyover works well for strangers or people you don’t know well yet. This is the version we used as examples in prior sections of this chapter. This story depth also works well for group social interactions or when you’re looking to make your point in an interview or on a first date.

Real-world example: “I had a pretty tumultuous childhood. My family lived in cars, and I went to eleven schools growing up. As you can probably tell, I’ve had some interesting experiences.”

Short, sweet, and to the point. The flyover is meant to supply the listener with a flavor of who you are while piquing curiosity, hinting at adversity, and leaving things open for questions. It’s enough to let people know you’ve been through some adversity without alienating them or making them uncomfortable. We touched on this idea previously.

The next level is intended for use when you’re ready to share and go deeper in a relationship with someone. You decide when to pull this version out and put it to use but be mindful—using this version too soon can backfire if your relationship doesn’t have the foundation to handle it.

Jump Altitude

Explanation: Flying at ten thousand feet. The ride is a little bumpier. From this height, you can make out some smaller landmarks and recognize the topography in more detail. You’re flying along at a medium speed, and the people on the plane know and understand they’re on a jump plane. From this height, when you make specific reference to your obstacles, some of those details will be more visible from here.

Jump altitude stories are typically for people you know a little better. This might be work colleagues who you’ve gotten to know over time or acquaintances who are on the path to becoming friends. This level also works on those fourth or fifth dates when you’re really diving in or engaging in some intimate pillow talk. It’s much more personal.

A real-world example might sound like this:

Real-world example: “Growing up, we were really poor. We moved around a lot and lived in cars as often as we did in homes. We often went without food and lived day to day to get by. I went to eleven different schools. For example, when I was in third grade, I went to three separate schools in that same year. We were always on the move because my father was an alcoholic and couldn’t hold down a job. We never paid the rent when we did have a house for a while. I swore I would never turn out like that, and from an early age, I set a different path for myself.”

In a few sentences, you can share much more of your world with someone. You can give a little more detail and keep things relatively distant for yourself. Only you know the grittier details of your story at this depth. You share enough to give your audience the true flavor of the adversity you’ve endured while still holding back the nuance and details that might embarrass you or them. Use this version to test their curiosity level. Experience suggests that most people will have a lot of questions at this point. They also often share their own story with you on a similar or comfortable level for them. This lets you direct the conversation where it’s naturally going.

Finally, we get to the most personal version. If you jump out of the plane at ten thousand feet together, you find yourself in an even more personal situation.

Tandem Landing

Explanation: Jumping and landing. This is the freefall you get from strapping on your parachute and hooking up tandem with someone. It’s a wild ride falling from the sky. You start your story at the jump door and continue as you jump from the plane. For your tandem passenger, the freefall is exhilarating, but you calmly pull the parachute and float to the ground. By the time you land, you can see and touch things on the ground as you walk around, exploring the new terrain together and independently.

If you’ve ever jumped out of a plane with someone attached to you, you know that the experience is very intimate. Similarly, this story’s depth is meant only for people who you know well or believe you can trust. These are generally friends or established acquaintances, who will appreciate and value your story at its most granular level. They won’t judge you for what you’ve been through and may have a story of disadvantage of their own to share. These are folks who are engaged and supportive of you via empathy and are possibly becoming better attuned or beginning to advocate for you. A great example would be romantic relationships as they progress.

This is the story depth where you should be prepared to answer questions and explain the nuance of your story in much more detail. The more you share, the more questions others will have.

While you can keep any boundaries you need to, you should expect others who landed with you to be curious, to explore, and to want to know much more about your story. These are rare occurrences and should be treated with the right care and diligence.

More detail at this level might include the following:

Real-world example: “I was the oldest of six, which made me the focus of my father’s drunken rage. He would hit me and push me around all the time. We finally moved out of the van we had been living in for a few years. This time, we moved into a beat-up old camping trailer for a few years in Maine in the middle of the woods with no running water or electricity. We had a wood stove for heat, and my brother and I had to cut down trees every day to stay warm. I remember one time when my father got angry about something I had done and pushed me into the hot stove, burning my arm and hand. I never forgot how much that hurt emotionally and physically.”

As you can see, you’re really getting into the nitty-gritty details of your underdog story at this level. These are the most intimate details of your trauma or disadvantage. The level of detail is much more granular and supplies added context for what you’ve been through and overcome. At this stage, you can be more direct as you no longer need to allude to things—you can supply the specific details, either voluntarily or when prompted by probing questions.

As always, the facets you share are up to you alone. This is your story and your relationship. You’re in full control of the elements you provide.

Your story should demonstrate who you are and what you’ve been through and should highlight your character. Getting good at sharing at these three levels can take time and practice. Remember, never share aspects of your story that make you uncomfortable and share only at the proper level for your audience. When in doubt, don’t provide more insights than you’re comfortable sharing. The only caveat is that you may need to push your comfort limits to get things rolling. Many underdogs struggle with exchanging any details about themselves, which is harmful in its own ways.

Ultimately, these are only guidelines to consider how to build deeper relationships with potential advocates across time. Share intelligently. Avoid oversharing. Trust your instincts.

Be willing to trial and error this strategy; take your time and see how it makes you feel. In time these various depths will flow naturally for you. Remember, sharing your story with others should be a mutual exchange. You’re going to vulnerable places only when it’s OK for you to do that so that you can build rapport, relationships, and advocacy. In return, your audience gets to bask in the awe of your story as they get to know you more intimately.

Additional resources to help you craft your story can be found at https://www.underdogcurve.com.

Sign up for the only newsletter exclusively for underdogs like you.

Once a week we deliver you one new underdog concept, framework, or insight along with a practial way for you to implement it into your life - for free!